The end of easy money: what to watch out for at the Bank of England’s Super Thursday

Global stock markets have tumbled in the last 24 hours, with the Dow Jones seeing its sharpest fall for six years. European markets aren’t far behind; the FTSE 100 has slipped to its lowest level in over nine months. Investors are nervous that loose monetary policy has pumped up asset prices. As central banks remove this stimulus, it’ll become clear that many companies have been overvalued.

Following these dramatic events on Wall Street and in the City, this week all eyes will be on the Bank of England’s ‘Super Thursday’ – when the Bank’s monetary policy decision coincides with its quarterly Inflation Report. With the world’s media watching the tightrope act officials at the Bank are attempting, as they try and wean us off a decade of easy money, the cracks in the UK economy will be on display.

So as Thursday approaches, here are three themes to watch out for.

1) Back to normality?

‘Normalisation’ is the buzzword of the hour. Following the 2007-08 crisis, central banks around the world slashed interest rates and deployed so-called ‘unconventional’ monetary policy, including quantitative easing (QE) – the vast expansion of the central bank balance sheet to inject cash into the economy.

But whatever central bankers might like to claim, there is nothing remotely ‘normal’ about our current economic situation. Cheap credit and so-called ‘portfolio rebalancing’ (when those who sell bonds to the central bank replace them with other financial assets) have driven relentless asset price inflation. House prices and stock markets alike have reached vertiginous heights.

After almost a decade of lax policy, central bankers are cautiously applying the brakes. The US Federal Reserve leads the pack, having taken the bold decision to start unwinding its QE programme in September 2017. The BoE is dragging its feet on unwinding (the MPC voted in November to keep the stock of bond purchases constant), but is some way ahead of the European Central Bank, which is still flooding markets with 30 billion euros a month.

No-one knows what will happen when central banks unwind QE while raising interest rates. Doomsayers fear that the ‘end of easy money’ will cause chaos. As bond yields artificially depressed by central bank purchases start to rise, investors will reevaluate the price of other assets, with the potential to cause a crisis. Stock markets in the US, which only last month were at historic highs, have already lost their nerve, suffering their biggest crash in six years. European markets aren’t far behind. The rising cost of debt will also hurt firms looking to refinance that hitherto have survived on cheap credit.

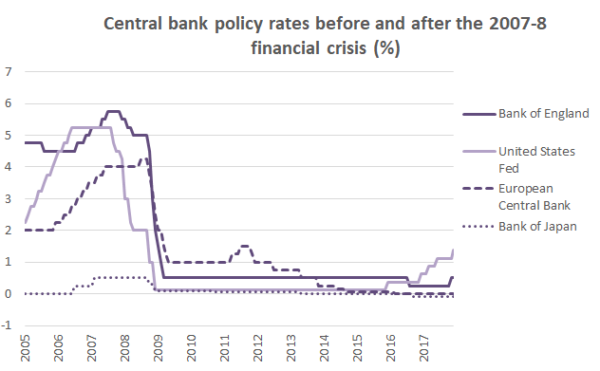

The global recovery could be over mere months after getting underway. Alarmingly, central banks are nowhere near the position they were in the last time crisis hit the developed world and so have little room to manoeuvre. Policy rates are still extremely low in comparison with 2007.

Interest rates set by central banks in advanced economies are still very low (source: Bank for International Settlements)

In the UK, hampered by uncertainty over Brexit, the problem is compounded by faltering growth and weak investment. Meanwhile, households have suffered the worst decade for real wages since the early 1800s. The Bank of England fears raising rates too fast in case it kills off a fragile recovery, and almost certainly won’t go for full normalisation just yet. But with rates so low, it has no good tools to use in the event of another crisis, however small. Until the MPC chooses to think outside the box and help ease the pressures on public investment, its policy conundrum is here to stay.

2) Will productivity show any signs of life?

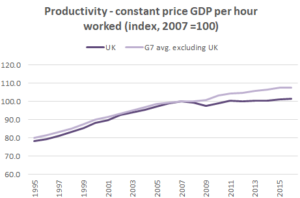

The Bank remains determined to raise rates partly because of its assessment of the UK’s productivity puzzle. Since the 2007-8 financial crisis, the UK economy has seen hardly any improvement in labour productivity – the amount of output it makes for every hour someone spends working – even compared to other G7 countries.

Since the 2007-08 financial crisis, productivity in the UK economy has flatlined (source: ONS)

Productivity matters to the Bank because it influences how much ‘spare capacity’ there is in the economy for demand to grow. If it is likely to pick up, then demand has space to expand without causing inflation; if it remains weak, then inflationary pressures will start to bite.

On this, members of the MPC are divided. Some, like Silvana Tenreyro, think productivity is due to pick up soon. If so, the Bank can keep rates lower for longer. Others are more hawkish. In a speech delivered the same week as Tenreyro’s, Michael Saunders argued that ‘there is little sign’ of productivity growth picking up enough to counterbalance a tighter job market. The latest unemployment figures, down to 4.3% for three months till November, will surely sharpen this view.

Yet, as Martin Sandbu wrote in the FT after the November rate rise, the biggest pitfall for the Bank is to ‘box itself in’. The MPC’s decision was needed mostly to save face and satisfy the markets after promising a rise for several months. But those promises were made in light of ‘particularly pessimistic’ forecasts for productivity. Working out the likely path for productivity is one of the Bank’s greatest challenges, and it needs as much flexibility as possible as the economy navigates choppy waters.

3) Will the Bank wake up to our household debt time bomb?

November’s rate rise wouldn’t have been so controversial if production was all that mattered. But as Sandbu observes, the flip side to the MPC’s productivity pessimism is its over-optimism about demand – and in particular, about household consumption.

Many UK households, to put it lightly, are in a pinch. For a start, consumer credit is looking unstable. All else being equal, tighter monetary policy will see interest repayments take up a larger chunk of households’ disposable income. After years of easy credit, households are now finding it harder to borrow – according to the Bank’s Credit Conditions survey in Q4 2017, the availability of unsecured credit (i.e. excluding mortgages) to households fell in every quarter of 2017. In its November Inflation Report, the Bank even drew attention to consumer credit as a financial stability risk, albeit with a reminder of its small size (just some 11% of household debt).

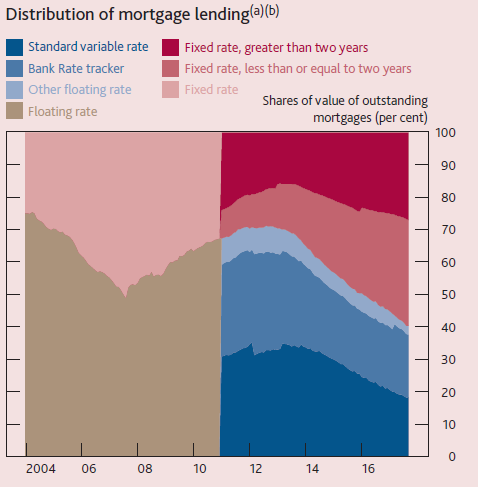

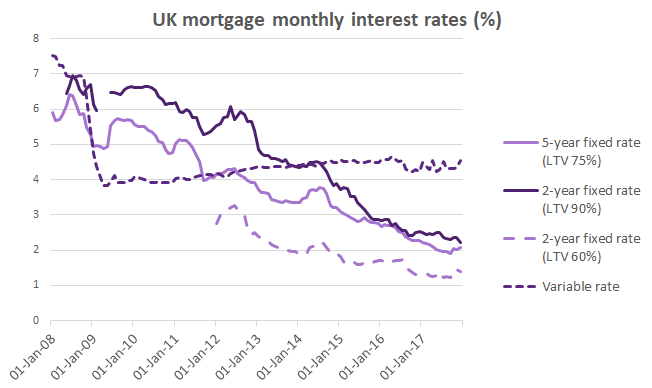

Of greater systemic importance are changes taking place in the housing market. Here, too, there is good reason to be apprehensive. The Term Funding Scheme – technically a part of the Bank’s QE programme, extending low-interest loans to banks to coax them to make their own in kind – will come to an end in February. Rates for fixed-rate contracts, which represent a growing share of mortgages in recent years, have fallen steadily; a sudden turnaround may cause a jolt. And in December statistics showed house prices static or falling, so people will feel less wealthy. These two factors combined could batter consumption.

A growing share of mortgages are fixed-rate contracts (source: Bank of England Inflation Report, November 2017)

Interest rates on fixed-rate mortgages have fallen significantly during the period of unconventional monetary policy (source: Bank of England)

The Institute for Fiscal Studies recently published findings on ‘problem debt’, particularly among low-income households. A crucial takeaway was that ‘entry into servicing pressure [being unable to make interest repayments or spending more than a quarter of income on such payments] is much more likely to be explained by a rise in debt servicing costs than by a fall in income.’ In other words, interest rate rises can hurt.

Though differences remain, the debt time bomb in the UK is a reminder of the economy pre-2007. What the economy needs is to be unhooked from unsustainable, debt-fuelled growth, without tightening the screws too suddenly. How the Bank of England handles this dilemma could help avert a crisis, or spell disaster. On Super Thursday, we’ll get a better idea of which way we’re headed.