Are we finally getting a pay rise?

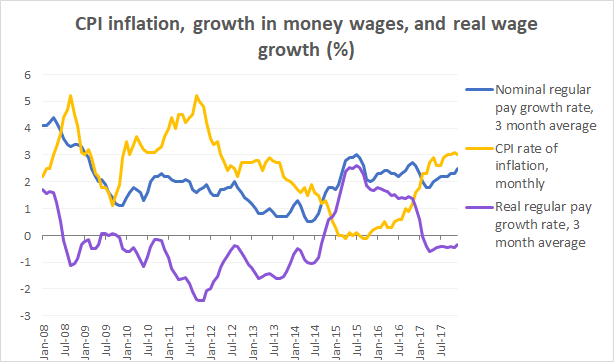

The past decade has been a dismal period for workers in the UK. Real wages have been in decline for much of the period since the financial crisis, eroding living standards and squeezing households. Only a flirt with deflation between 2015 and 2016 eased the pressure; since 2016, due to inflation from a weaker pound, real wages have been falling once again.

Officials at the Bank of England think things have changed. In last week’s Bank’s quarterly Inflation Report, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) estimated that nominal wage growth will pick up over the first half of this year. If true, this good news would also mean monetary policy can tighten faster than previously anticipated. Unfortunately for workers and policymakers alike, nothing is certain.

Source: ONS (series may not sum due to differences in measurement)

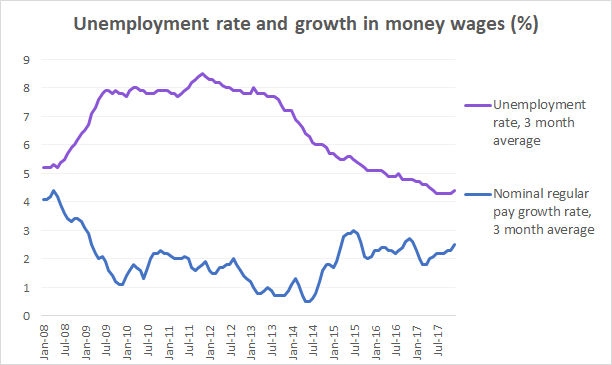

The poor wage growth of recent years is a puzzle. Theory suggests that low unemployment should increase workers’ bargaining power, driving employers to offer bigger pay packets. But though more and more people are in work, this has not been matched by rising pay, even in nominal terms. After a slight recovery in 2015, earnings growth has levelled out, despite unemployment falling to a level not seen since the 1970s.

In early 2017, MPC suggested several reasons for this anomaly. One was weak productivity growth: firms can’t pay their workers more if they don’t make enough revenue from each hour of labour they hire. They also argued that the falling price of food and energy during 2014 and 2015 (that near-deflationary spell in the chart above), meant household budgets had more space to breathe, and softened their demands for higher wages.

Source: ONS

By the Bank of England’s own analysis, weak productivity can’t account for all of the poor growth in earnings. Moreover, the Brexit vote has seen import inflation hit the UK fairly hard since 2016. Even if households had anywhere near the bargaining power the MPC suggests, we would expect them to have been pressing for higher pay over the past two years. Something else must responsible for some of the terrible earnings performance.

The MPC’s answer to this concerns so-called ‘slack’ in the labour market. Slack is like spare capacity. As unemployment falls, the labour market ‘tightens’ and wages start to pick up. But this depends on the level of the lower bound for unemployment beyond which further falls will cause inflation. The Bank terms this the ‘equilibrium unemployment rate’. Estimating the equilibrium rate is crucial for making monetary policy decisions.

The MPC keeps updating its view on this central question. It lowered its estimate a year ago, from 5 to 4.5%. Given unemployment stood at 4.3% in January 2018 and wage growth has hardly budged, the MPC would be hard pressed to stick to that figure. Accordingly, this February, the committee brought its estimate down another notch to 4.25%. To back this up, the Inflation Report points to the absence of any increase in long-term unemployment due to the recession. It also argues that a better-educated workforce and flexible contracts mean more jobs are now being created than destroyed.

Will these predictions turn out in the data? Analysts have been watching closely for stats on jobs and earnings released today by the Office for National Statistics. The results have been a mixed bag. Regular earnings (i.e. not including bonuses) have enjoyed growth of 2.5% – not stellar, but but moving in the right direction. Yet unemployment has moved back up from a fairly constant 4.3 to 4.5%. Some analysts have suggested this is due to people joining the labour force, rather than being made redundant, as the total number of full-time jobs also increased. But the turn in the data captures the difficulty the MPC faces in making its forecasts.

What’s troublesome is that the MPC has a poor record on that forecasting when it comes to wages in particular. Every year between 2014 and 2017, the February Inflation Report projected wage growth that simply didn’t manifest. The 2016 forecast put earnings growth at over 3% by 2017; in reality, it slumped the following year, recovering to 2.5% only in October. This time around, the MPC points to a rise in pay settlements shown in by the Bank’s Agents’ annual pay survey.

A factor the Bank doesn’t like to talk about is the ascent of the ‘gig economy’. Lots of people are technically in employment, but not as we know it. They’re in low-paid, sometimes part-time, insecure jobs. The oblique reference in the Inflation Report to ‘increased flexibility in the labour market’ picks up on these trends. But a new normal in the labour market for many people means that the old models linking earnings to employment probably don’t work like they used to.

The danger is that the MPC misses a structural change in the economy weighing on household incomes and raises interest rates too fast, extinguishing a nascent recovery. Until real wage growth moves into positive territory, there’s every reason to be sceptical about the recovery Bank officials want us to see.