To better understand UK banks we have to follow the money

From how UK banks create money to how they managed to lose so much of it in the last crisis, there are some persistent misconceptions that must be challenged. A bank’s privilege is not only its ability to create credit but also its ability to take deposits which are guaranteed by the state. With this assistance, all UK bank profits can be explained as the result of a taxpayer subsidy. Instead of passing on some of this subsidy to benefit the real economy, UK banks instead use it to inflate house prices and fund other financial speculation. The activities of UK banks are therefore increasing the risk of the next economic crisis.

If our banks can ‘create money out of thin air’ then how can they go bust?

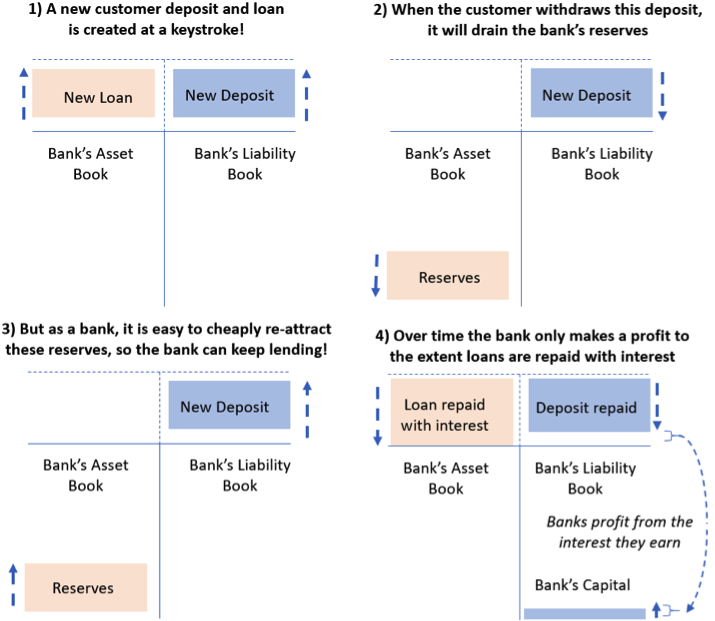

Our banks only create money when they make new loans. In exchange for the customer’s promise to pay the money back (a loan agreement) a bank simultaneously grants the customer the right to withdraw money (this is equivalent to having a deposit). In effect, the bank has created both anti-money and money. The process can only profit the bank to the extent the created loan will be repaid with interest:

Through time, these interest payments are what enable a bank to increase how much it owns (the value of all its loans and mortgages, and its reserves) against how much it owes (the value of all its deposits and other debts). This profit increases the bank’s capital (this is the difference between the bank’s assets and liabilities owed to its shareholders).

But let’s imagine the loan instead defaulted. Now, what the bank is owed (i.e. its assets) would fall with no matching decline in what it owes (i.e. promised deposits etc). The bank’s shareholders would no longer profit from interest; instead, they would suffer a fall in their capital. Therefore, while it’s true that banks ‘can create money out of thin air’, they will only do so to the extent they can make profitable loans. Or they will go bust, which happens when their liabilities are bigger than their assets.

So why did UK taxpayers have to bail out banks by £133bn[1] in the last crisis?

Heading into 2008, UK banks’ capital bases were extremely small relative to the size of their asset books. This meant there was only a tiny cushion of equity to absorb any losses. Only a few loans needed to go bad before some banks went bankrupt (i.e. to owe more than they owed). When this happened, the UK government chose to inject huge amounts of new capital into these banks. Otherwise, they would have had to close their doors and liquidate their assets at fire-sale prices. This would not have raised enough money to pay back a bank’s depositors in full. If even one bank’s depositors lost some of their money, this would have likely triggered a run on all banks, causing financial mayhem. A taxpayer bail-out was considered the least bad option.

What limits the UK bank sector’s ability to lend?

There are actually only two real constraints to stop banks creating an infinite amount of new money through lending. Having enough reserves to lend out is not one of them. In short, banks can always make a loan and then find reserves later. The first constraint for bank lending is the need to find willing borrowers who the bank expects to pay the money back with interest. The second constraint is the bank’s capital adequacy ratio – which measures whether the bank has enough of a capital buffer to absorb possible losses on assets (designed to protect the government from having to bail out the bank to protect its depositors):

These two constraints together explain why bank lending is so pro-cyclical. In boom times banks lend a lot, as many borrowing opportunities seem profitable, and their capital grows as few loans default. But in recessions, there are fewer willing profitable borrowers, and capital bases suffer write-downs on loans that go bad; banks will always stop lending when we need them most.

So is our money in the bank really ‘money in the bank’?

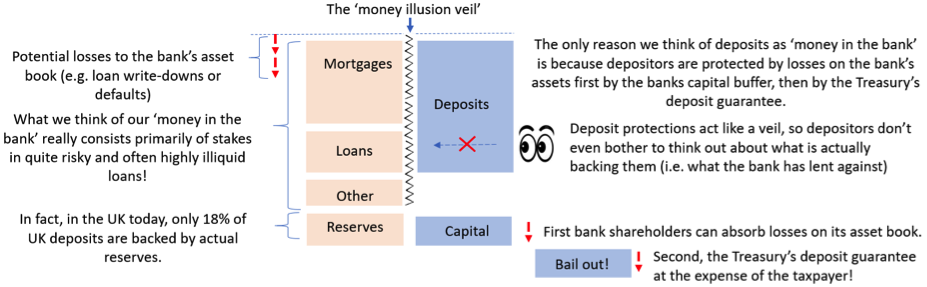

No. Today only 18% of UK bank deposits are backed by reserves. The remaining 82% of deposits are instead backed by banks’ illiquid, and often risky, mortgages and loans. The happy fiction in which we believe our bank deposits are totally safe and accessible is only due to the immense protections afforded to them by the state. The Treasury guarantees our bank deposits against losses (on each account up to £85k) and the Bank of England (BoE) effectively guarantees we can withdraw them at any time:

So how do UK banks acquire this privilege?

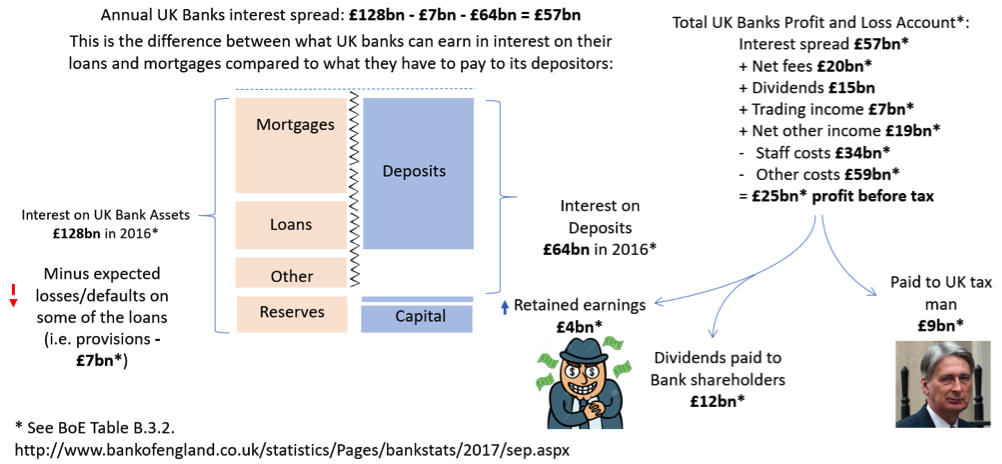

A bank licence grants a bank the right to accept deposits. This is their true source of power. Because when a loan is created and the debtor withdraws their claim on funds, the bank doesn’t have to worry about its reserves draining. Unlike with normal capital markets (such as equity or bond financing), a bank knows it will be able to cheaply re-attract any reserves it needs. Due to the Treasury’s deposit guarantee, and complete access to our money (backed by the BoE) people are perpetually willing to return reserves to banks at low or even zero interest. In fact, the difficulty of holding cash means deposits rarely leave the banking system at all. This enables a healthy interest spread between what the bank receives as interest on its loans compared to what it has to pay on deposits. This is their main source of profit[2]:

If government protection means banks can pay less to their depositors, isn’t that like a subsidy?

There’s no other UK sector which enjoys such explicit backing by the state if its activities fail. It’s hard to imagine an auto company being able to sell cars on the basis that the government will promise to fix them in case of a major breakdown! We can calculate just how much this protection is worth annually to UK banks: It’s the extra interest banks would have to pay their depositors if the Treasury removed its deposit guarantees (i.e. we might lose money if the bank failed) and the Bank of England stopped guaranteeing our permanent access to funds.

The New Economics Foundation produced an excellent and detailed analysis of this calculation. But put very simple, few people would be prepared to still hold their money in a bank on these worse terms without being paid at least a couple of extra percent interest. Multiplying this increased cost of deposits by UK banks deposit base of roughly £2.3 trillion (see diagram later in this piece) this works out to an annual subsidy to UK banks of £46bn[3] (£2.3tn*2%), almost UK bank’s total interest spread. And considerably more than the entire current annual profits of UK banks can be explained as a subsidy (£25bn Pre-tax Profit < £46bn pa subsidy).

Doesn’t this subsidy help UK banks provide cheaper credit to companies?

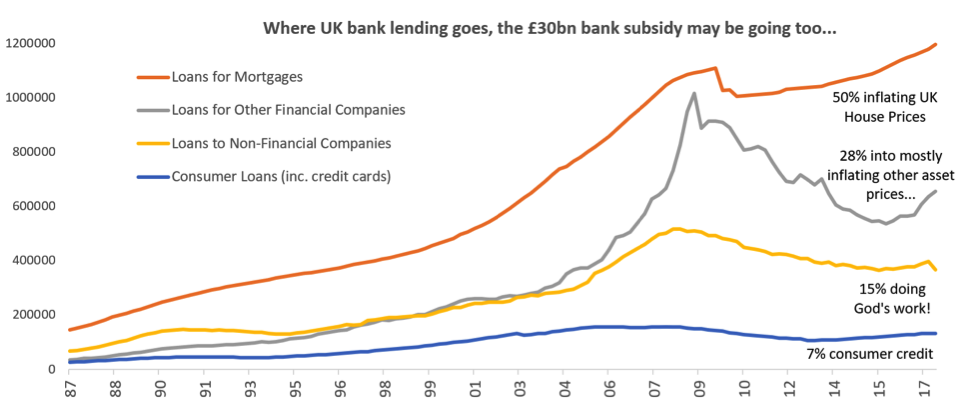

In the last crisis, Lloyd Blankfein defended Goldman Sachs activities as doing God’s work: ‘We help companies to grow by helping them to raise capital. Companies that grow create wealth’. Might some of the £46bn UK bank subsidy, not just boosting profits, be helping reduce the cost of bank credit to businesses, thus promoting jobs and economic growth?

But in reality, only 15% of credit from UK banks actually flows to non-financial businesses (of which only a third goes to SMEs – see BoE Table A.8.1.). And this figure has actually fallen significantly over the last decade. If the £46bn bank subsidy is helping to lower the cost of borrowing at all, it is primarily helping fund cheaper mortgages or other lending into financial speculation:

Source: BoE Table A.4.3. and note that due to changes to reporting of securitised loans, the amount of mortgages outstanding for Q1 2010 was reduced by £62bn. For further break-down of NFC lending, see Table A.8.1.

Although cheaper mortgages might seem to benefit those buying houses, they do the opposite. They mainly help cause rising house prices by increasing demand (with less than 20% helping to fund new-builds[4]). Therefore, to the extent government deposit protections are having this effect, it can be stated that today the UK taxpayer is directly subsidising its housing bubble:

Source: BoE Table Mortgage change + Nationwide

What do UK bank balance-sheets look like today?

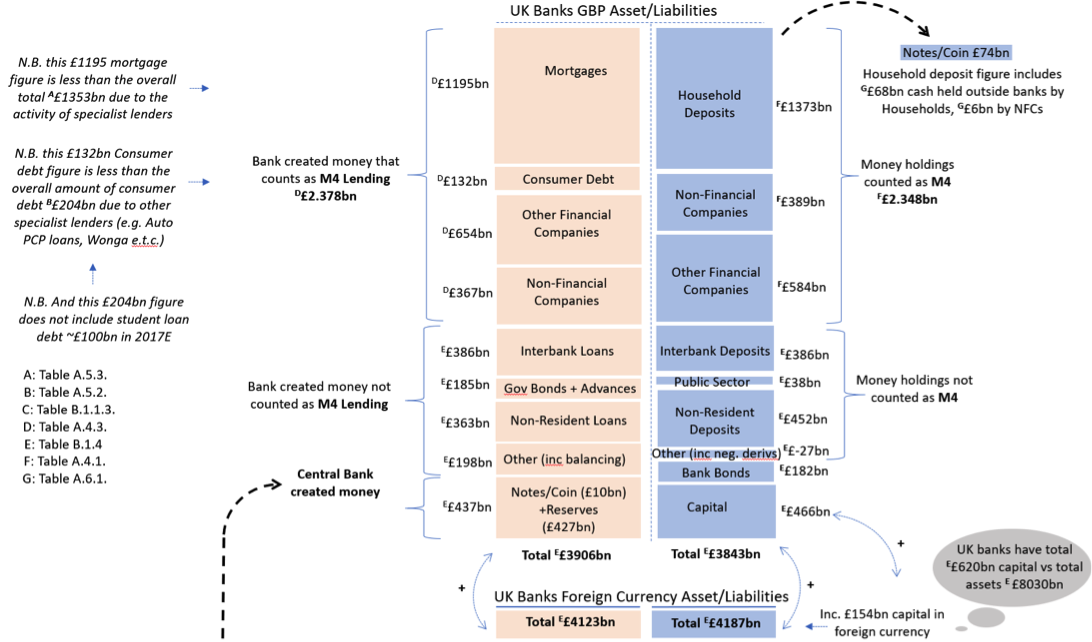

Only a full picture of UK banks’ total assets and liabilities can give us a sense of how UK banks have been operating, and what risks they’ve taken at the taxpayer’s possible expense. Using information from multiple BoE data sets, the current situation can be revealed[5]:

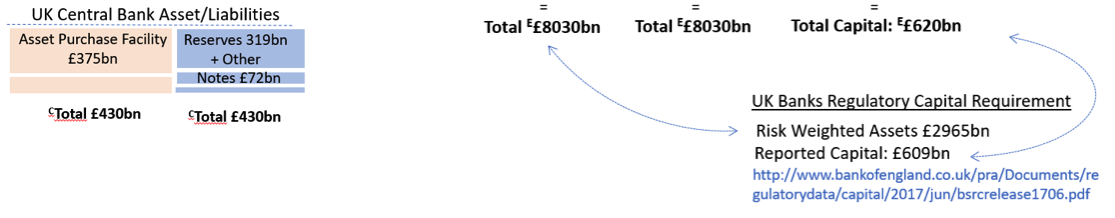

These numbers capture all banking operations conducted out of the UK (i.e. both UK-owned and foreign-owned banks). Including activities denominated in foreign currencies, total UK bank exposure is £8 trillion, with a capital buffer of £620bn. Note this figure approximates with the BoE’s reported regulatory capital[6].

But if we wish to instead focus solely on the balance sheet of UK-owned banks (n.b. BoE Table B.1.4.1.1. excludes foreign-owned banks) these figures shrink to £450bn of capital versus £4110bn of assets. This helps us to identify the current risk which they’ve exposed the UK taxpayer of over £3 trillion (calculated as the ‘assets at risk’ (£4110bn – £95bn of government bonds – £247bn reserves) minus the bond and capital buffer (£270bn commercial bank bonds + £450bn capital) = £3050bn).

Today’s higher regulatory capital requirements (compared to before the last crisis) have reduced the risk UK banks will need a bailout from the taxpayer. But we’ve still done nothing to change the basic nature of how they operate: UK banks are helping to push up asset prices (primarily houses) in good times, only to risk driving significant declines in bad times. Higher levels of debt owed to banks raise the sensitivity of household or corporate spending to any fall in income, threatening to worsen any downturn. Finally, pro-cyclical bank lending risks turning any recession into a full-blown economic crisis. In the words of Adair Turner ‘we’ve better-protected banks against the economic cycle, but we’ve not yet protected the cycle from the banks’:

[1] https://www.nao.org.uk/highlights/taxpayer-support-for-uk-banks-faqs/

[2] Data is from BoE ‘Bankstats’ Sept 17 Release: www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/Pages/bankstats/2017/sep.aspx

[3] This should not be confused with the ‘too big to fail’ subsidy which gives large banks the ability to also pay lower interest on their bonds or other financial liabilities (as it’s believed they wouldn’t be allowed to go bust).

[4] https://www.cml.org.uk/industry-data/key-uk-mortgage-facts/

[5] Especial thanks to Sam Maynard at the Bank of England who was incredibly helpful in answering my questions.

[6] http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/pra/Documents/regulatorydata/capital/2017/jun/bsrcrelease1706.pdf

The BoE suggested the discrepancies (e.g. £620bn vs £609bn reported) because ’these numbers are compiled at the highest level of consolidation and reported by PRA regulated firms. So they include amounts held by subsidiaries and associates, non-financial firms engaged in ancillary activities, joint ventures and other non-PRA regulated entities’