QE 101 (Part 2): How Does the Bank of England Create New Money?

A lot of people can go their entire lives without asking themselves how money is created and where it comes from. On the other hand, as the Bank of England noted, many modern day economic textbooks provide a flawed description of money creation. In any case, the concept of money creation can be tricky to grasp.

For these reasons, many people (including journalists, politicians, and even economists) might be confused by the Bank of England’s Quantitative Easing (QE) money creation programme.

So as a part of our beginner’s guide to QE, we thought it might be useful to just go over how the Bank of England creates new money under this £445bn programme (for QE 101 (Part 1): What is Quantitative Easing click here).

Central Bank Reserves

In the current monetary system, 97% of money consists of bank deposits (i.e. the electronic figures you see when you check your bank account) while the other 3% is made up of coins and banknotes.

Most people know that the government, through the Bank of England and the Royal Mint, issue two kinds of money: metallic coins and paper banknotes. But the Bank of England also issues electronic central bank reserves.

Central bank reserves are sometimes seen as an electronic equivalent of cash. But central bank reserves are special because the general public doesn’t have direct access to them. So people can hold cash, but they cannot hold central bank reserves.

In fact, it is mainly private commercial banks and building societies that are allowed to hold central bank reserves. The Treasury and a few other strategically important finance companies also have access to them.

These reserves are held in electronic accounts at the Bank of England – and only the Bank of England can create them.

The reserve accounts held by private banks at the Bank of England are very much like the current accounts people hold at their own bank.

In the same way that people make payments by exchanging cash or through electronic bank transfers, banks settle payments amongst themselves with central bank reserves. They simply transfer central bank reserves between their accounts at the Bank of England (for a more in depth explanation of how money is created please click here).

Creating Central Bank Reserves (Normal Times)

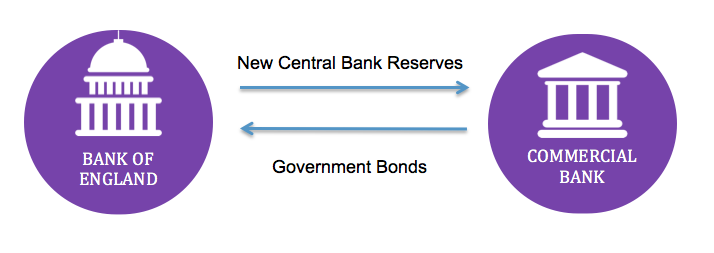

In normal times, if the Bank of England wants to inject new central bank reserves into the banking system, it can do simply by purchasing some bonds (i.e. government debt) held by commercial banks.

To buy the bonds, the Bank of England credits a commercial bank’s reserve account with the brand new reserves it creates.

In effect, the Bank of England creates new central bank reserves and trades it with the commercial bank for bonds. The commercial bank swaps the bonds it held for new central bank reserves. This process is known as ‘repurchase agreements’ (repos) or more traditionally as ‘open market operations’*.

Creating Central Bank Reserves via QE

For the purposes of this guide, we can say the QE programme is really only different from traditional open market operations in two major ways:

The scale and size of QE is significantly larger than conventional open market operations.

QE also involves the Bank of England buying government and corporate debt (in the form of bonds) from non-bank investors (e.g. pension funds, insurance companies, investment banks, foreign investors etc.), rather than just from commercial banks

The second point here is fundamental. Under QE, the Bank of England buys bonds from both banks and non-banks. This is important because as the above explains, non-banks cannot hold central bank reserves. But obviously, they are going to want something for the bond they are selling to the Bank of England.

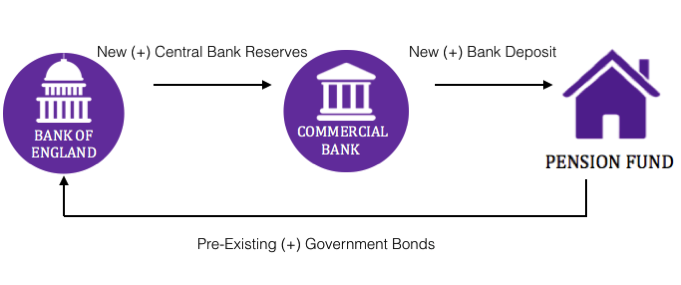

So what happens when non-banks – let’s say a pension fund – sell bonds to the Bank of England?

The answer is the pension fund gets money credited into its current account at its bank. That pension fund will get newly created bank deposits. The Pension Fund’s holding of government bonds is reduced, but it receives an increase in its current account in exchange.

This is because the Bank of England credited the reserves account of the Pension Fund’s commercial bank with newly created reserves. These reserves then become the property of the commercial bank, (in financial jargon they become the asset of the commercial bank).

But in return, the commercial bank increases the Pension Fund’s account by the amount of central bank reserves received. This account is a liability of the commercial bank (a promise to pay or an IOU), so the bank does not end up better or worse off as a result of the transaction (because it now has an asset as well as a matching liability).

Conclusion

In sum, the Bank of England’s QE programme always involves the creation of new central bank reserves which are exchanged for some sort of financial asset (i.e. government or corporate bond). When the Bank of England creates new central bank reserves and purchases financial assets from banks, no new bank deposits are created in the process.

However, under QE, the majority of the time the Bank of England creates new reserves and buys financial assets from the non-banking sector (i.e. pension funds and insurance companies), in which case new bank deposits are also created in the process.