Inflation & The Bank of England’s New Catch 22

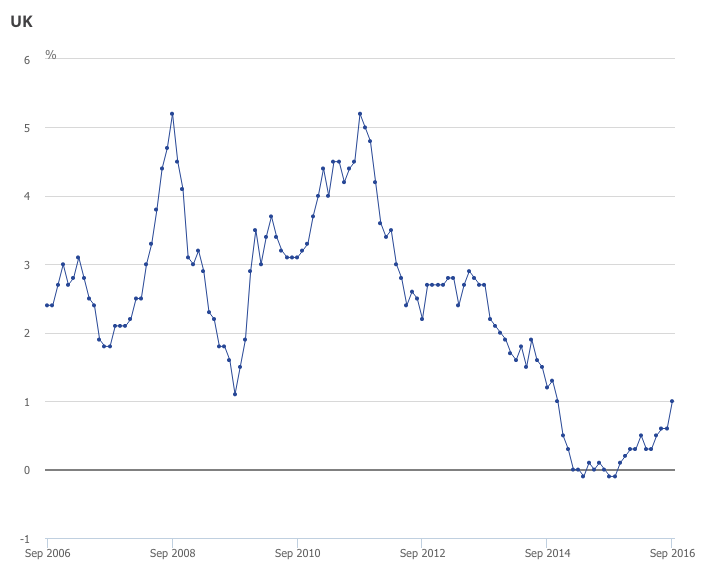

The British inflation rate for September increased faster than expected to 1% – a two-year high – primarily due to rising prices for clothes, hotel rooms and petrol.

While a weaker pound may not explain the latest rise in consumer prices, is the cost of living expected to increase in the future? And what does this mean for the Bank of England?

Increasing consumer prices and a weakened sterling

With everyday consumer prices increasing from 0.6% in August to 1.0% in September, we have witnessed the biggest month-on-month jump in prices since June 2014.

With the value of the pound dropping by nearly 20% against the US dollar since Britain voted to leave the European Union, prices of British imports are expected to increase.

Therefore inflation is expected to continue to rise sharply in the months ahead as higher import prices feed into consumer prices, which will lead to a higher cost of living all round.

For example, last Friday, Governor of the Bank of England (BoE), Mark Carney, said things are most likely going to “going to get difficult” for the people on lowest incomes as the prices of food begin to increase.

However, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) suggested the weakness of the pound was yet to influence import prices, and thus didn’t explain the latest rise in consumer prices.

Instead, the rise in prices can be primarily explained by: 1) the rise in clothes prices, as shops begin to bring in their autumn ranges; and 2) the impact of falling energy prices beginning to fade.

UK 12 Month Inflation Rate

Why haven’t the costs of importing goods and outsourcing production fed into a higher cost of living?

Firstly, while the ONS has suggested that the Brexit vote and a weaker pound have not yet fed into higher import prices, the feud between supermarket giant Tesco’s and Britain’s largest food manufacturer Unilever begin to suggest otherwise. The feud came about because Unilever wanted to increase prices by nearly 10% to compensate for the falling value of the pound.

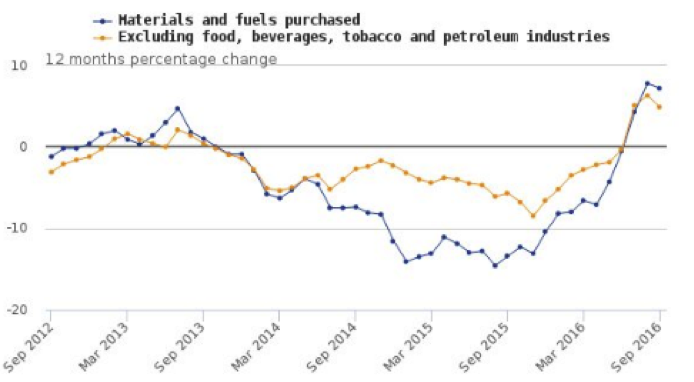

Indeed, as the chart below shows, many companies are already being charged more for their materials since the pound has dropped.

Price of UK Raw Materials

Secondly, in the short-term most businesses will have specific measures in place that will protect them against changes in exchanges rates. This is why it may take a few months for the weak pound to feed into higher import costs.

The BoE suggests that it could take up to a year before the effects of a weak pound start to feed into prices, with fuel prices being the first to go up, followed by gas and electricity and then other goods such as food.

The danger of higher costs of living

The danger with higher consumer prices is that they will not be matched by increases in wages, which would depress real incomes.

Indeed, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has demonstrated that the jump in inflation will cost poorer households (those on benefits) about £100 each, simply because benefits will remain the same while prices will increase.

The same applies to people’s wages. If prices go up but wages stay the same, then the purchasing power of wages will be less (you wont be able to buy as many goods and services with your wage).

The same premise applies to people’s savings. With very low-interest rates and rising levels of inflation, savers will be hurt. If interest rates are lower than inflation rates, then the purchasing powers of savings will be less.

Moreover, as we are still very much suffering from a weak recovery from the latest financial crisis, higher consumer prices may put people off spending. Less spending means less income for businesses and people, which could lead to more unemployment and even less spending – in a mutually reinforcing fashion.

The Bank of England’s Catch 22

The BoE has forecast that inflation will rise beyond the desired level of 2%. Governor Mark Carney recently said that he was willing to tolerate inflation “a bit” above the bank’s 2% target. But many economists are suggesting that inflation will increase more than ‘a bit’, and will more likely reach 3 – 4%.

This puts the BoE in a bit of bind. Normally, to curb inflation the BoE would raise interest rates. But ‘normally’ too much inflation is a signal that the economy is at full capacity and in danger of overheating. That too many people are borrowing, investing, and spending – which pushes prices up (for a simple explanation of inflation and the BoE’s interest rate policy click here).

The problem is that this is definitely not the case – for the last eight years interest rates have been at historical lows. Indeed, the BoE recently reduced interest rates because it is worried that the Brexit vote will create uncertainty, which could lead to even less borrowing, spending and investment. Therefore, the BoE expects the economy to be running below full capacity.

So the Bank of England has to deal with an extraordinary scenario where inflation will be higher than desirable, whilst the economy is running below its capacity. As external MPC member of the BoE, Michael Saunders recently said:

“This is really the first time that the MPC has clearly faced the prospect of an inflation overshoot amidst continued slack at the 2-3 year horizon”

The BoE, therefore, doesn’t want to raise interest rates to curb inflation, because the economy won’t be running at full capacity. Indeed, raising rates could lead to a stock market crash, as well as depress spending and investment in a time of great economic uncertainty. Moreover, as the economy is still struggling with a private debt overhang (people already struggling with debt repayments), even a small rise could prove unaffordable.

The Bank is more concerned about getting the economy to run at full capacity. Accordingly, many economists are suggesting that BoE may even cut rates further and could potentially further expand the £445 billion QE programme.

What should the Bank of England do?

The situation facing the BoE is definitely a tricky one. However, what is clear is that lower interest rates and QE will not help to stimulate spending – and will only increase inequality and financial instability. Instead, the BoE should cooperate with the Treasury, and finance a fiscal stimulus with newly created money (click here for an explanation of how such a programme could work).

Indeed, as professor of macroeconomics Roger Farmer suggests, a fiscal stimulus financed by new money would give the Bank of England the option to stimulate spending whilst simultaneously raising interest rates. Of course, this wouldn’t solve all the BoE’s problems, but it could go a long way in helping the BoE out of its catch 22 predicament.