Global debt reaches $152 trillion – We need an alternative!

Global debt has more than doubled in the last 15 years; and according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), it’s the highest it’s ever been.

Is it any surprise that in the last 40 years we have had some 150 systemic banking crises and 70 sovereign debt crises?

Indeed, the Bank of England recently suggested that private debt is one of the biggest threats to the UK economy. And yet the Bank has just introduced policies (lower interest rates and an expanded QE programme) designed to encourage even more borrowing and debt. In fact, these policies are designed to reinforce the same lending that led to the financial crisis.

We clearly need better ways of stimulating growth, boosting people’s incomes, and financing the necessary infrastructure investment for a green economic transition. We need an economic strategy that does not rely on increasing private or the net level of public debt.

Global debt

In a new report, the IMF warned that public and private debt – excluding the financial sector’s – at the end of last year hit $152 trillion. With two-thirds of this owed by the private sector, the rest of it is public debt.

But debt in of itself is not necessarily a bad thing. In Western economies, the primary problem is that the bulk of this debt is not being used for productive purposes (i.e. to boost private sector incomes, finance infrastructure and a green economic transition). Indeed, in the UK over 80% of bank lending goes into sectors that don’t directly contribute to an increase in productivity.

Current debt levels now sit at a record 225 percent of world gross domestic product (GDP). This clearly demonstrates that lending is not boosting productivity – and is being used increasingly inefficiently. When lending increases as a percentage of output/income, it means that the amount of lending that generates a unit of output/income has risen*.

The point here is that the sheer volume of debt is not as much of an issue as the debt to output/income ratio. The latter is a more important gauge because it gives a better indication of whether: 1) the debt is helping boost incomes; 2) people and businesses can afford to take out more loans; 3) whether the debt can be repaid or not.

Private debt and financial crises

The IMF’s report suggests that there is no general consensus on what precise level of debt to output/income leads to financial instability. However, the fund did state that financial crises are primarily caused by excessive levels of private debt (while public debt does not increase the probability of financial crises – it matters to sovereign crises).

Significantly, the IMF also notes that private debt booms are not only the cause of financial crisis, but even when crises have been avoided, excessive levels of private debt can lead to economic slumps. This is because if private incomes do not increase at the same rate as private debt, borrowers will eventually have to reduce their consumption and investment in order to service their debt – and will not be able to borrow.

The Bank of England’s policies

In response to increasing economic uncertainty prompted by the recent Brexit vote, the BoE has just announced its new monetary stimulus package. With seven years of interest rates at their lowest point in history, interest rates have been cut even further from 0.5% to 0.25%.

A fresh round of QE is also taking place with £70 billion being added to the current £375 billion programme. This time round, however, the BoE will buy up to £10 billion of corporate bonds and just £60 billion of government bonds.

The monetary policy package is intended to get the private sector to alter its borrowing and spending behaviour.

Before 2009, the BoE had never cut rates below 2% and since then, they haven’t increased above 0.5%. Cutting rates to 0.25% is unprecedented. It is ultimately intended to convince people to spend today what they would’ve spent tomorrow – but the other side to that is the build-up of private debt, which creates headwinds for the real economy.

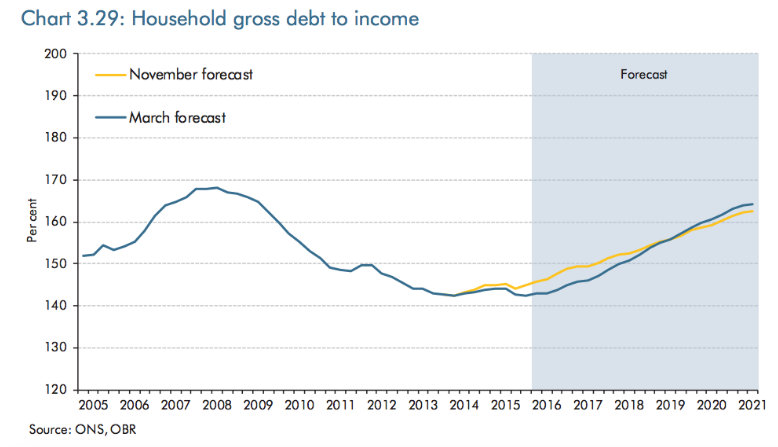

But even before these policies were introduced the OBR in March said Households are expected to spend £58bn more than they earn this year, rising to £68bn by the end of the decade. The report further stated:

“The persistence of a household deficit of this size would be unprecedented in the latest available historical data”.

In fact, just a month before the Bank of England’s policy announcement, the Bank identified high household debt as the biggest risk to the UK economy.

If our primary tool to prevent a financial crisis and potential recession is to encourage more bank lending and thus more private sector debt, we should be worried. Indeed, encouraging more debt onto an overly indebted private sector is effectively a ‘hair of dog strategy’.

We need an alternative

The massive level of global debt clearly illustrates why we need to rethink our economic policies. These “hair of the dog” strategies show the extent to which the Bank of England’s monetary policy toolbox needs to be updated. We need other more fair and sustainable policies, which do not rely on increasing private debt or public net levels of debt. We need money creation for the public.

A public money creation programme would fundamentally allow governments and the private sector to pay down debt without reducing investment and spending in the economy. Meanwhile, money could be directed into the productive sectors of our economy – for example by financing the necessary investment in infrastructure for a green economic transition.

*A very simple example is if £1 of debt produced £1 of output/income in one year, and £2 of debt produced £1 output/income in the next.