Bank of England, if old tools don’t work anymore, consider new ones

With recent data showing that economic conditions seem to be deteriorating, the Bank of England is expected to lower its UK growth forecasts and come up with a stimulus package to aid the UK economy. Instead of cutting interest rates or pumping more electronic money into financial markets – resulting in higher levels of household debt – the Treasury and the Bank of England should seize this opportunity to cooperate. The Treasury should support the design of alternative monetary policy tools, so that the Bank of England can use its power to create money to finance a fiscal stimulus.

UK Economic Conditions deteriorate at fastest pace since 2009

Recent data from a respected survey of private sector companies shows that the Brexit vote has brought about the worst drop in business confidence since the last financial crisis, according to data from Markit.

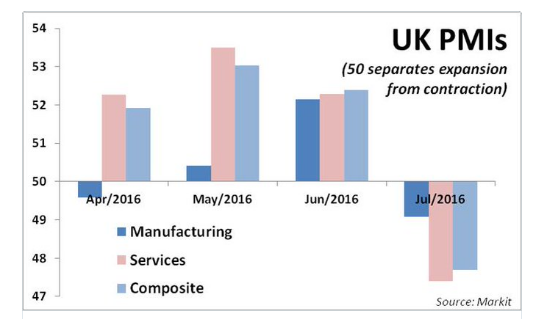

The early edition of the Purchasing Managers’ Index indicated that the services sector dropped from 52.3 in June to 47.4 in July (anything below 50 indicates contraction). The manufacturing PMI fell from 52.4 to 48.2, while the composite index, which combines services and manufacturing, fell from 52.4 to 47.4 – the weakest readings since April 2009.

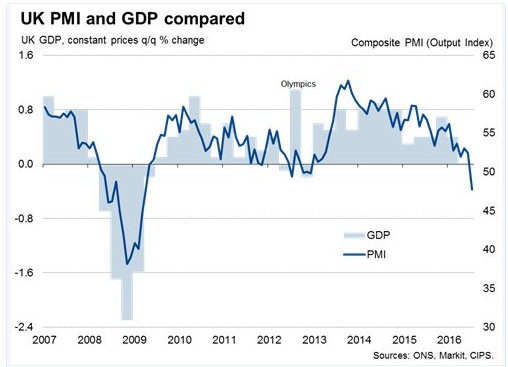

The PMI is one of the leading indicators for growth in the UK economy, successfully predicting the 2008 recession, and the stagnating growth of 2012 – as the graph below shows. Indeed, if past trends are anything to go by, there seems to be good reason to believe that turbulent economic times lay ahead.

Monetary Policy Response

While there is the potential of overreacting to the Brexit vote, the Bank of England will most likely respond to the above data by cutting interest rates from their historic of 0.5%, and it could potentially pump more money into financial markets via Quantitative Easing (QE).

But as Larry Elliot notes:

“Interest rates have been at 0.5% for more than seven years, so cutting them to 0.25% or even 0% is not going to do much. Likewise with another £50bn worth of QE, on top of the £375bn that was pumped into the economy during the Great Recession, and the years that followed.”

Indeed, if anything these policies will most likely result in higher levels of household debt – currently one of the most significant risks to the UK economy, according to the Bank of England. In effect, the thing that poses the biggest risk to our economy is being used as the primary solution to a crisis. As we argued earlier, this type of ‘hair of the dog’ strategy is unsustainable and only jeopardizes financial stability.

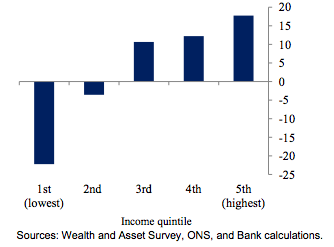

Indeed, it is more likely that these policies will do little more than increase inequality by increasing the prices of assets – which will bring further threats to financial stability. It is hardly surprising that since 2010, those in the bottom 40% of the income distribution have seen virtually no increase in their wealth (in fact their wealth has fallen), while those in the top 20% have seen their wealth increase by nearly 20%.

Wealth Gains by Income Quintile Since 2010

Fiscal Policy Response

Meanwhile, according to journalist Larry Elliot, “The Treasury is also gearing up to provide stimulus measures.” Chancellor Phillip Hammond has suggested that he will be ‘resetting’ fiscal policy. With economic conditions looking uncertain, and the private sector’s reluctance to invest, the Treasury needs to step in and provide much needed investment.

With very low interest rates, there is an argument that now is a great time for the government to borrow and invest in infrastructure. For example, as Professor Lord Robert Skidelsky suggests:

“But now, when real interest rates are almost zero or negative, is the ideal time for governments to borrow for capital spending. Bondholders shouldn’t worry about debt if it gives rise to a productive asset.”

Alternatively, economists at Merryl Lynch recently suggested, the Bank of England could cut VAT from 20% to 17.5% – the same measure taken by former prime minister Gordon Brown in 2009. According to Giles Moec at BoAML, this would help offset the hit to consumers’ pockets from the recent 12 per cent depreciation in sterling, and would come at a fiscal cost of 0.7% of GDP. This would reduce tax revenues by £12.5 billion over the course of a year but, according to the convention that governments should borrow only to finance new investments, this would have to be met by expenditure reductions elsewhere.

Monetary and Fiscal Cooperation

At Positive Money, our position is that the government can borrow money (but doesn’t have to) from the financial markets if it wants to finance a fiscal stimulus. However, we also believe that if indicators suggest that there is spare capacity in the economy, that aggregate demand is below a certain threshold – to the extent that price stability is endangered – then the Bank of England should step in. It should work closely with the Treasury to proactively create new money to finance a fiscal stimulus up until indicators for aggregate demand reach the desired threshold.

As Eric Lonergan rightly puts it, we need to “strengthen the armoury of central banks, to whom we have delegated the counter-cyclical heavy-lifting.”

But there are other reasons for not solely relying on bond financing (government borrowing) for such a countercyclical stimulus. Chancellor Hammond has said that he would only announce changes to the budget in autumn. If such changes involve more infrastructure spending, then it will take some time for this spending to stimulate the real economy. By the time these measures kick in, the economy could already be in a recession.

On the other hand, if the government decides to go down the more immediate route and cut VAT – then this could result in an increase in the budget deficit by 0.7% of GDP. We welcome these measures as they will help stimulate the economy. However, if they are only financed via government borrowing it may leave the Government with very little room for any further fiscal expansion (i.e. via green infrastructure investment or affordable house-building) down the line. There is a very good chance that there will be political pressure in the future to fiscally tighten (i.e. reduce public spending or raise taxes) – although there doesn’t necessarily have to be. This may minimise possibilities for the investment in infrastructure or affordable housing which so many people desire.

Thus, while interest rates are low and the government can benefit from low borrowing costs, with the UK in disinflation territory and aggregate demand below its desired level, the Treasury should update the monetary policy tools available to the Bank of England. The Bank of England should finance some of the countercyclical fiscal stimulus that this country needs to nurse the deteriorating economic conditions – but only until aggregate demand reaches its desired level (to find out more about how this can be done click here).