Inflation and the Bank of England’s Catch 22

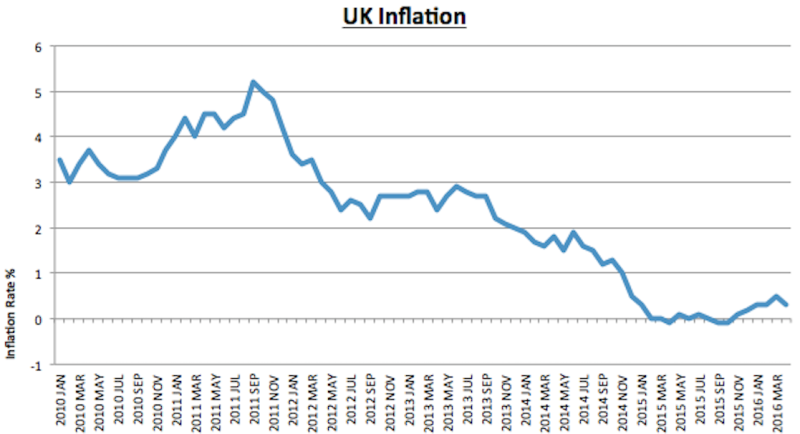

After a slow but steady increase since October, the UK rate of inflation fell to 0.3% in April from 0.5% in March, deviating from the expectations that economists had pencilled in. What triggered this decline? And more importantly, what are some of the headwinds in the face of monetary policy?

Inflation in the UK

The inflation rate, a measure of changes in the price of consumer goods (loosely defined as the final products that shops sell, such as food, clothing, and cars) had, since October, been showing a very slow but steady increase. Indeed, many economists had expected prices to be increasing at an annual rate of 0.5% in April.

Since 2014, persistently low levels of inflation have been largely due to the drastic reduction in oil prices. However, core inflation, which strips out measures such as energy and food, also fell – from 1.5% to 1.2%.

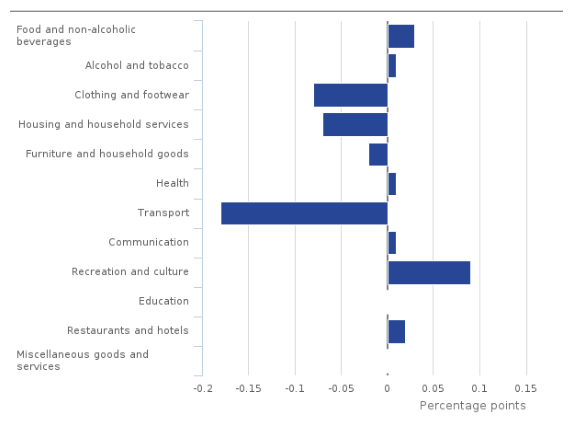

According to the ONS the recent decline in the inflation rate is due to:

“Falls in air fares and prices for clothing, vehicles and social housing rent were the main contributors to the decrease in the rate.

These downward pressures were partially offset by rising prices for motor fuels and for certain recreational goods and cultural services, and by food prices, which were unchanged between March and April 2016, having fallen between the same two months a year ago.”

Whats Driving UK Inflation?

Bank of England Interest Rates & Monetary Policy

As previously discussed on this blog, the primary mandate of the Bank of England (BoE), is to deliver price stability – low inflation, defined by the government’s inflation target of 2%.

The BoE attempts to influence consumer prices by altering the ‘base’ rate of interest on the reserves that banks hold at the BoE. In turn, this is intended to change interest rates that banks charge their borrowers, changing the level of debt and money created by the private banking sector.

Lowering base rates is intended to stimulate private sector borrowing and lower the cost of servicing current debt – which according to mainstream theory, should lead to more private sector spending, and a general increase in prices.

Conversely, higher interest rates should reduce demand for new loans and increase the cost of servicing existing loans (that are not on fixed rates), leading to a reduction in private sector spending, and a general decrease in prices.

Headwinds at the Bank of England

Policymakers face a number of headwinds when calculating and judging whether a rate change is necessary. One of these headwinds is that low interest rates may stimulate aggregate demand, but at the expense of higher asset prices (especially housing) and even asset price bubbles. In contrast, a rise in rates could curb the rise in asset prices and prevent potential bubbles from emerging or growing. But any rate rise could depress aggregate demand and prompt a decline in prices – sending the economy into deflation territory.

This catch-22 situation might only get worse as time goes by. On the one hand, the manufacturing sector contracted for the first time in three years, due to “lacklustre trends in production and new orders and declines in both employment and stocks of purchases”.

Meanwhile, the ONS has suggested that construction output – accounting for 6% of the economy – fell 3.6% on the month in March – the biggest drop in 4 years.

Indeed, in its most recent inflation report, virtually all of the Bank of England’s forecasts suggest that the economy will perform slightly worse than it had previously expected (this is based on the premise that the UK will stay in the EU). Forecasts for growth, productivity, household income, and employment were all downgraded.

According to mainstream economic theory, keeping interest rates low – or even cutting interest rates further – is necessary to prevent further slumps in growth, productivity, households’ incomes, etc.

But on the other hand, a number of indicators suggest that it might soon be time to raise rates. In its first-quarter credit conditions review, the Bank of England pointed to the growth in consumer credit, and highlighted the growth in car loans and an increased level of mortgage lending.

In fact, at a property investment conference last February, the Bank of England’s deputy governor for financial instability, John Cunliffe, warned that:

“We remain vulnerable to the resumption of the rates of credit growth, driven by the housing market, seen in the 10-year upswing of the last cycle.”

(Unfortunately, deputy governor Cunliffe is suggesting that higher house prices drives demand for high levels of lending. Note, he is not suggesting that higher levels of lending can lead to higher house prices – we’d be celebrating at Positive Money if that were the case!)

Meanwhile, Samuel Tombs, chief U.K. economist at Pantheon Economics, has stated:

“Lending standards are slowly loosening … encouraging borrowers to take on even bigger loans. The stronger growth in credit is one thing that is going to be concerning the MPC (at the Bank of England)…Banks are taking increasing risks now with their lending”.

Indeed, banks are extending the terms offered for mortgages – the average mortgage is no longer for 25 years, but closer to 35 years. A number of banks have also increased the upper age limit at which they will lend – an 85 year old can take out a loan at Nationwide. Alice Martin of NEF, has noted how Barclays has launched a no-deposit, 100% mortgage scheme.

Ultimately, this all suggests that it may be more prudent to raise rates then to keep them at their all time low – let alone lower them even further.

The Catch-22

Thus, it is clear that the Bank of England faces a catch-22 situation. Low interest rates might be necessary to stimulate the economy, but at the expense of higher asset prices. Meanwhile, higher rates may be needed to prevent asset prices from increasing, and to curb the excessive risk taking that the banking sector seems prone to.

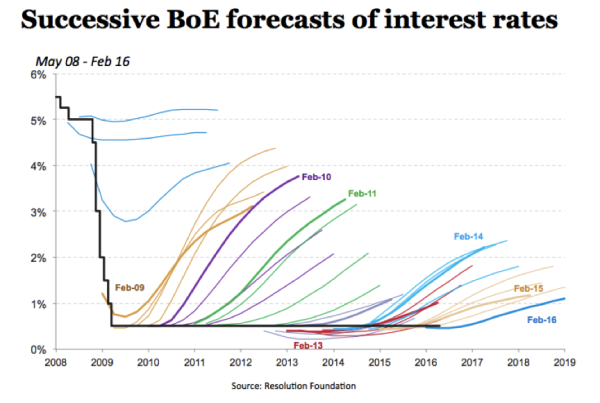

Accordingly, it is hardly surprising that the Bank of England has not been able to successfully forecast interest rate changes for the last 8 years. The Bank of England’s inability to accurately predict its own change in interest rates, coupled with the above catch-22 situation, epitomises the current limitations of the policy ‘toolkit’ available to central banks and the dearth of ideas within mainstream policy making.

To address this deficit in ideas, and to consider whether new monetary policy tools could stimulate the economy without inflating asset prices, Positive Money advocates the establishment of a money commission.