BIS Warns of a Global Debt Crisis and a Lack of Policy Response Options: Time to Update the BoE’s Policy Toolkit?

The Bank for International Settlement (BIS) has just warned that the global economy faces a “gathering storm” brought on by too much borrowing. With high levels of private debt relative to income, increasing financial volatility and poor prospects for growth there are growing concerns about the lack of policy response options available to central banks.

But is there a way to reduce dependence on debt, restore market confidence, and diminish financial instability, whilst growing the economy in a sustainable way? Is there really a lack of policy options available? Or is it simply time to upgrade the policy toolkit available to the Bank of England (BoE)?

Debt at the heart of it

In its latest quarterly report, BIS Chief Claudio Borio suggested that there is an “uneasy calm” giving way to “turbulence”, which threatens to transform into a full on “storm”. However, the cause of this turbulence is not due to some random financial shocks or uncontrollable exogenous events. Rather, the common threat underlying all this turbulence is private debt:

“If we wish to look for clues to the deeper forces at work, we need to go beyond the markets’ all too familiar oscillation between hope and fear. Once we do so, the clues are not hard to find…Debt was at the root of the financial crisis, and it has risen further globally in relation to GDP since then…”

(Source: BIS)

Debt as the engine of global growth

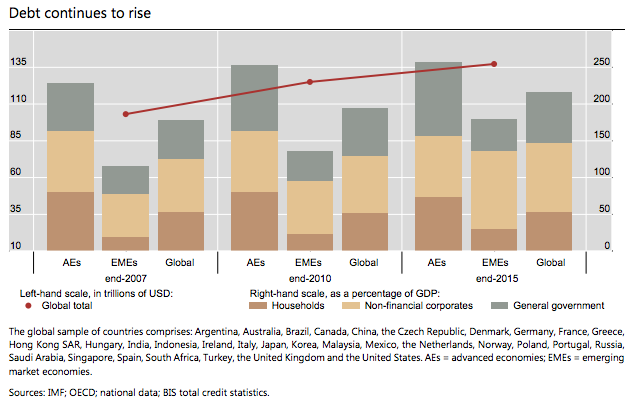

The BIS chief notes that total accumulated debt is higher today than it was before the start of the last credit crisis in 2008. The global economy has taken on $57 trillion since the previous financial crisis, with about $200 trillion of debt outstanding in the world economy producing about $80 trillion of new goods and services annually.

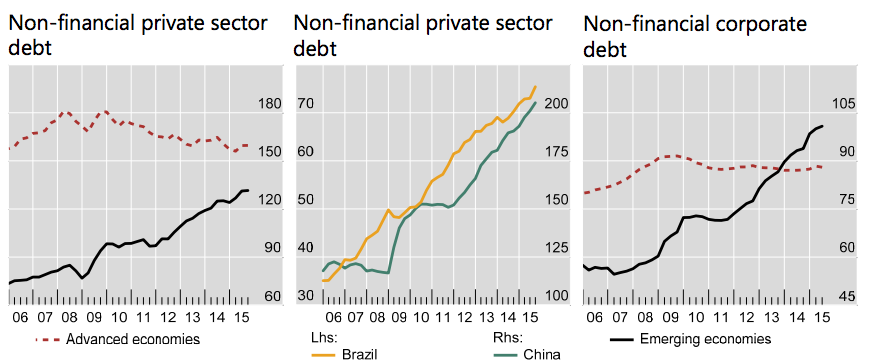

Indeed, Borio makes the point that the majority of this debt has been taken on by emerging economies, which have been “the main engines of global growth post-crisis”. But in the third quarter of 2015, demand for new lending began to dwindle in these economies and this “sheds light on the [economic] slowdown of emerging economies”. Since then, prospects for global growth and trade have substantially weakened.

Corporate debt in Emerging economies

(Source: BIS)

Debt and the productivity puzzle

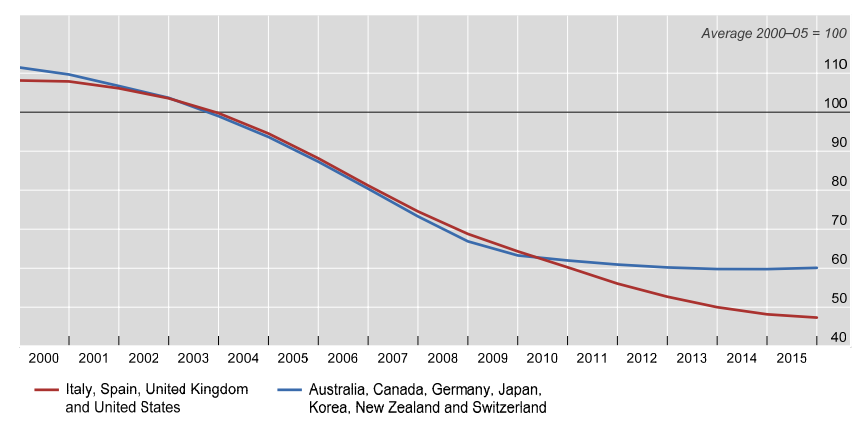

But high levels of debt don’t only explain the global economic slowdown, they also help explain the productivity puzzles plaguing many advanced economies today:

“And it may [high levels of private debt] even illuminate the puzzling slowdown in productivity growth: recent BIS research finds evidence that credit booms sap productivity growth as they gather pace, largely by allocating resources to the wrong sectors. The impact of these misallocations lingers on and becomes more powerful if a financial crisis subsequently erupts. In turn, weaker productivity makes it harder to sustain debt burdens.”

The global decline in productivity

(Source: BIS)

A lack of available policy options

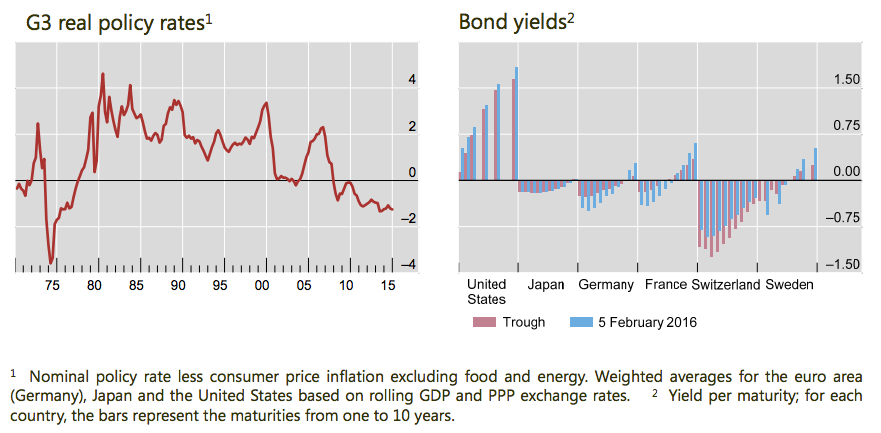

Accordingly, with their private sectors over-burdened by debt, Borio makes the point that central banks are running out of policy options and markets are beginning to notice:

“And then we have the narrowing room for policy manoeuvre. The latest turbulence has hammered home the message that central banks have been overburdened for far too long post-crisis, even as fiscal space has been dwindling and structural measures lacking. Despite exceptionally easy monetary conditions, in key jurisdictions growth has been disappointing and inflation has remained stubbornly low. Market participants have taken notice. And their confidence in central banks’ healing powers has – probably for the first time – been faltering.”

Interest rates have been exceptionally and persistently low

(Source: BIS)

It is here where we have a much less gloomy view than Chief Borio. With public sector borrowing costs at an all time low, due to loose monetary policy, there is still significant room for fiscal manoeuvre in many countries. Moreover, as Lord Turner has pointed out, structural reforms can have a contractionary effect in the short-term.

But more importantly, there are policy options available to central banks – their toolkits merely need an update.

Updating the BoE’s Policy Tool Kit

If indicators suggest that there is spare capacity in the economy, that aggregate demand is below a certain threshold – to the extent that price stability is endangered – then the BoE should be able to step in. However, the current tools available to central banks – namely interest rates, quantitative easing, forward guidance – are not proving successful at stimulating aggregate demand.

The toolkit available to the BoE therefore needs to be updated, so that it can proactively create new money to finance government expenditure up to the point where indicators for aggregate demand reach the desired threshold.

Thus, while interest rates are low and the government can benefit from low borrowing costs, with the UK in disinflation territory and aggregate demand not at its desired level (despite cheap oil prices and increasing real wages) the Bank of England should be creating money to finance expenditure. This is why we suggest using Sovereign Money Creation to stimulate the economy.