The Story of Our Economy in 2015: A cocktail of household consumption, household consumption, and more household consumption

Debt-fuelled consumption underpinned economic growth in 2015. Without upgrading the policy ‘toolkit’ available to the Bank of England, the UK economy could come undone in the years to come.

Increased household spending, financed by soaring levels of consumer debt and the lowest savings ratio in history, continued to drive the UK economy in 2015. Our unbalanced economy and continued reliance on increasing household debt to fuel growth will most likely end in economic disaster. Policymakers need to begin thinking outside of the box and should consider taking measures to slow down money creation by banks – complemented by QE for People.

Growth and Consumption in the UK

When adjusting for inflation, growth in 2015 is now likely to have slowed to 2.1%, compared to 2.9% in 2014. A breakdown of the figures for GDP by expenditure demonstrates unbalanced growth, with continued dependence on household consumption.

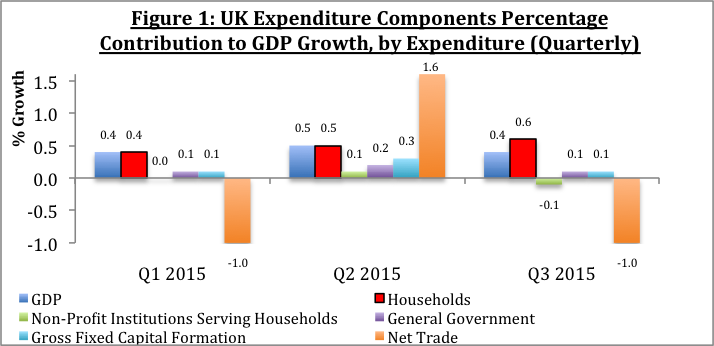

Household spending made up 64% of total GDP expenditure in 2014 – and it still continues to grow faster than any other expenditure category. Figure 1, shows the quarterly contribution of the expenditure components to growth of GDP in chained volume measures. Throughout the year, the largest positive contribution to GDP came from household spending (growth in net trade was highest in the second quarter but was offset by the preceding and following quarters).

Quarterly measurements show that household final consumption has increased consecutively for the last 9 quarters; and when compared to the same quarter a year earlier, household consumption has been increasing every quarter since 2011 (Figure 3 below).

Speaking to the Financial Times, Andrew Simms, director of the New Weather Institute, said that his greatest concern about the balance of the recovery was “it has none…Any talk of recovery now is like saying that a previously paralytic alcoholic had recovered because he’d found the strength to lift a new bottle to his mouth.”

(Source: ONS)

Household Savings and Borrowings

What has been fuelling the growth of household consumption? In part, more people are working, thus more people are spending. Some might also emphasise the recent increase in real disposable income prompted by lower levels of inflation. But an increase in real disposable income cannot fully explain the higher levels of household consumption. Annual growth in real disposable income for the last three years has been 0.8%, and has been outpaced by growth in household expenditure, increasing at 2.5% per year in real terms.

To finance their spending, households have been dipping into their savings.

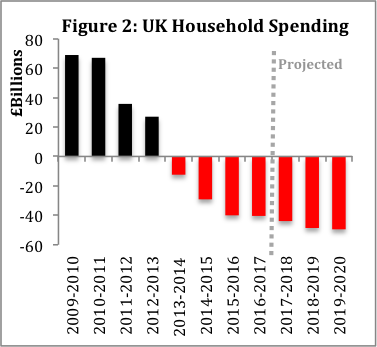

Figure 2 shows that just four years ago, UK households on aggregate were spending £67 billion less than they were earning. According to the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), households are now spending £40 billion p.a. more than they earn.

(Source: OBR)

(Source: Bank of England & ONS)

Indeed, at the end of the month, households are saving half as much as in 2012. The average savings ratio for 2015 was 4.6%, the lowest since records began in 1963. Figure 3 shows that the fall in the rate of household savings coincides with the increase in the rate of household consumption.

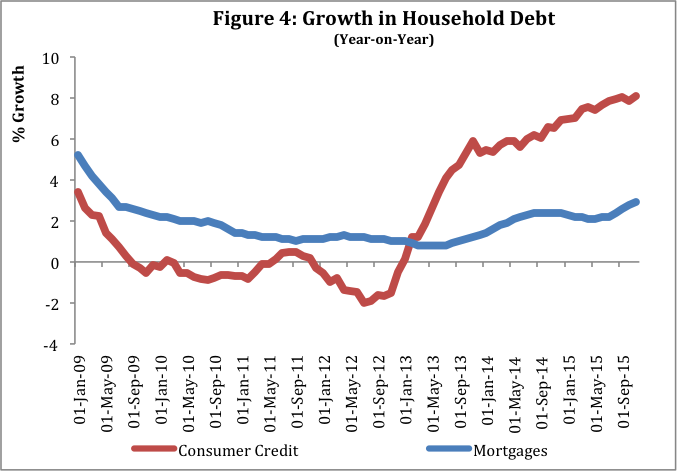

In addition, increasing household debt is helping to fuel consumption. With consumer debt growing at an annual rate of over 8% (Figure 4), £1.5 billion in November, this represents the biggest increase in consumer borrowing since before the crisis.

(Source: Bank of England Statistical Interactive Database)

The Years Ahead

The OBR forecasts that real GDP growth will average 2.3-2.5% a year between 2016 and 2020. This growth is meant to take place despite the reduction in government expenditure. As we have suggested before, considering that the UK is not a net exporter, if the government decides to reduce its level of debt then the domestic private sector has to take on more debt for there to be any growth. Increasing levels of private sector debt, (business and household borrowing), will be called upon to drive growth in the years to come.

However, early signals suggest that the business community is not as optimistic about their respective contribution to growth. Business activity in the last quarter grew at its slowest pace for more than two years – and long-term expectations for business activity were the weakest since 2013.

This coincides with a separate survey conducted by Deloitte, where the chief financial officers of Britain’s largest companies have reported a substantial rise in business uncertainty and have had to scale back their expectations for investment and hiring over the coming years.

When considering the future, therefore, our analysis suggests that economic growth will depend on the household sector taking on an unsustainable amount of debt. As Figure 2 demonstrates, the OBR projects that households will spend £40.4 billion more than they earn in 2016-2017, and another £43.9 billion in 2017-2018, £48.6 billion in 2018-2019, and £49.5 billion in 2019-2020.

The most recent report by the OBR indicates that household debt as a percentage of personal income will hit pre-crisis levels of 160% in 2019. Having over-estimated business confidence however, to achieve the projected levels of growth, households will most likely have to take on even more debt.

Monetary Policy

With a savings ratio at its lowest on record and the household debt re-approaching its pre-crisis peak, the Bank of England might be tempted to increase interest rates. According to mainstream economic textbooks this might be expected to increase savings and reduce consumer borrowing.

But the above suggests that a reduction in consumer borrowing would most likely dampen prospects for growth. Higher interest rates may further diminish business confidence and would increase the value of the pound, leading to a reduction of income on exports.

Moreover, our dependence on private debt to fuel growth has led us to a situation where households are financially stretched, and we should be worried about what households will do when interest rates rise. Over one third of mortgage loans have been taken out by households that have borrowed more than four times their income; while a sixth of it is held by those who have less than £200 a month left after buying daily essentials. In the meantime over 9 million Britons are over-indebted, half of whom are living in families on incomes below £20,000. Many households, especially those on lower incomes, could be in significant trouble if interest rates are raised.

This catch-22 situation demonstrates the current limitations and ineffectiveness of the policy ‘toolkit’ available to central banks, as well as, illustrating the dearth of ideas within mainstream policy-making circles. Policy makers should consider making the transition to a Partial-Sovereign Money System.

This would entail curbing levels of borrowing, without hurting the most overly-indebted households, by setting central bank reserve ratios for the private banking sector. To compensate for any contraction in household spending, triggered by the introduction of a reserve ratio, the Bank of England should create money and spend it directly into the economy. This type of QE for People would allow for spending to take place without a corresponding increase in the balance of net debt and without fostering further financial instability.