The Interest Rate Dilemma: Financial Crisis Either Way???

An awkward stand off has emerged amongst some of the World’s leading monetary policy-makers. On the one hand, the IMF has warned central bankers that in the face of low growth and deflation, increasing interest rates and stopping QE risks triggering another global crisis. On the other, a group of central bank governors countered the IMF’s stance, cautioning their policymaking peers that they risked precipitating the next crisis by extending the period of ultra loose monetary policy.

It would appear that either way, financial stability is tenuous at best – we might just be a crisis away from an era of stagnation and persistent deflation that parallels that of the 1930s Great Depression. Our current precarious economic situation coupled with the standoff between the IMF and central bankers demonstrates that policy-makers are ill-equipped – both intellectually and in terms of policy tools at their disposal – to deal with the complexity of present day economic challenges.

Accordingly, policy makers need to start thinking outside of the box, and add a Sovereign Money Creation (SMC) style of People’s Quantitative Easing to their toolkit. SMC would not only do a better job of stimulating aggregate demand, laying the foundations for robust economic activity, but it would do so in a far more sustainable fashion.

The Standoff

At the recent prestigious annual meeting between the IMF, the World Bank, and global central bankers in Lima (Peru), the limits of present day monetary policy could not have been made more apparent.

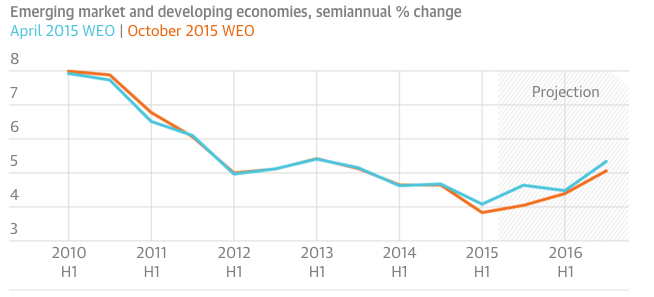

Forecast for Economic Growth: April 2015 versus October 2015

(source: IMF)

The IMF stated in last communiqué at the conference that financial instability and market uncertainty have recently intensified, whilst short and medium-term growth forecasts have been downgraded. More specifically, it said:

“In many advanced economies, the main risk remains a decline of already low growth, particularly if global demand falters further and supply constraints are not removed.”

To maintain and support global growth, the IMF suggested that Japan and the Eurozone should continue their quantitative easing programmes and that the US and UK maintain current interest rate levels:

“The recovery is expected to pick up modestly, supported by continued accommodative monetary policies, and improved financial stability…”

Interestingly, growth is allegedly supposed to be supported by both accommodative ultra-loose monetary policies and improved financial stability. The International lender of last resort evidently has somewhat of a paradoxical forecast, as it is well known that ultra-loose monetary policy does not go hand in hand with improved financial stability.

Indeed, this was the primary concern of a group of central bankers, who responded to the IMF’s stance by releasing a study that shows the current trend of ultra-loose monetary policy risks sowing the seeds for the next global crisis.

Four ex-central bankers, comprising the likes of Jean-Claude Trichet (former president of the ECB) and Axel Webber (former president of the Deutsche Bundesbank), specifically launched the publication of their study in Lima to coincide with the timing of the conference. Their study suggests that:

“The long period of extremely easy monetary conditions has not generated inflationary pressures in the advanced market economies (AMEs), as many initially feared. However, it might well have contributed to further misallocations of real resources in the economy, to reducing potential output, and to unsustainable increases in asset prices.”

However, the study does not only warn that accommodative monetary policies lead to financial instability through the unsustainable increase in asset prices. Ultra loose monetary policy also exacerbates financial instability by promoting higher levels of private debt, which then reinforces the need for even more monetary easing:

“The danger is that debt levels will rise with the passage of time, strengthening the arguments for still more forbearance (more loose monetary policy)…”

Accordingly, the quartet of central bankers take the opposite position to that of the IMF and suggest that central bankers need to tighten up and put an end to accommodative monetary policy:

“There seems to be widespread agreement that central banks must exit from these abnormal policies at some point…the modalities and implications of such an exit implies a bias toward this happening too late rather than too soon.”

Sovereign Money Creation – A New Monetary Policy Tool

The outlined standoff demonstrates the current limitations and ineffectiveness of the policy ‘toolkit’ available to central banks, as well as, illustrating the dearth of ideas within mainstream policy-making circles. Whether monetary easing is continued or eventually tightened, it seems that there is ample reason to believe that either policy route may lead to yet another crisis.

Regardless, of which policy route is taken, both sides have failed to recognise that monetary policy has failed in what it had originally set out to do, as highlighted by Larry Elliot of the Guardian:

“Ultra-loose monetary policy, together with tighter supervision of the financial sector, was supposed to minimise the risks of another crash while ensuring that plentiful supplies of cheap money boosted real activity. The opposite has occurred. Wages, productivity and growth have been poor even as investors have taken bigger and bigger risks in the search for high returns. In real life, they have been allowed to take us to the brink of ruin for the second time in less than a decade.”

As Adair Turner recently noted current monetary policy has wedged us into debt-trap, where the net burden of debt does not actually fall, it merely increases and shifts between different countries and different sectors. He thus concludes that:

“Seven years after 2008, global leverage is higher than ever, and aggregate global demand is still insufficient to drive robust growth. More radical policies – such as major debt write-downs or increased fiscal deficits financed by permanent monetization – will be required to increase global demand, rather than simply shift it around.”

Sovereign Money Creation would allow for such debt write-downs and could finance fiscal stimulus. SMC would directly trigger a significant boost in aggregate demand without a corresponding increase in the balance of net debt and without fostering further financial instability. Debt to income ratios would consequently be lowered, as the net financial assets of the non-government sector could be increased without a corresponding increase in private sector debt. With less debt relative to income, the financial system would be more resilient to potential financial volatility and shocks. Even if such a shock were to occur, SMC is a tool that would allow government’s to better respond to it.

More importantly, our economies would be more robust and growth more sustainable as monetary policy-makers would not have to solely rely on the interest rate channel to influence economic activity. Policy-makers would not be in the current catch 22 situations where they can either; continue loose monetary policy and increase private debt and asset bubbles, or tighten and risk depressing aggregate demand leading towards further deflation and low growth. Indeed, SMC would give policy-makers more options. For example, in the present situation, policy-makers could use SMC to compensate for any contraction in aggregate demand that resulted from a gradual rise in interest rates.

Ultimately, central banks need to upgrade their tool kits for managing crises and stimulating economic activity. Allowing SMC to supplement the interest rate channel would be a good start.