Breaking Taboos: David Graeber’s thoughts on the next crash

Setting out to break some of the deeply entrenched taboos pervading economics in Britain, David Graeber has written an excellent piece on why he believes that we are heading for another 2008 crash. While we do not agree with all the points raised in Graeber’s article, it does a great job of highlighting how fiscal policy can lead to dangerous levels of private debt and thus financial instability. Yet, fiscal policy, regardless of what political guise it takes, needs to be complemented by appropriate monetary policy – one which includes Sovereign Money Creation (a form of People’s QE) in its policy toolkit.

Sectoral Balances

The first taboo Graeber aims to break is that of fiscal policy and sectoral balances. Sectoral balances are not some form of economic theory; rather, they are ‘accounting identities’ that are essentially ‘based on very simple mathematics’. In concise terms, sectoral balances looks at the accounting structure of three sectors in every economy: the private sector, public, and external sector. The laws of accounting assert that in any economy the surpluses or deficits across these three sectors must add up to precisely zero.

This leads to Graeber’s primary point, that “the less the government is in debt, the more everybody else is”. The accounting identities of sectoral balances show that if one sector “goes up, the other must necessarily go down”. That is if the government starts running surplus, the private sector must run a corresponding deficit by taking on more debt, as Graeber explains:

“If the government declares “we must act responsibly and pay back the national debt” and runs a budget surplus, then it (the public sector) is taking more money in taxes out of the private sector than it’s paying back in. That money has to come from somewhere. So if the government runs a surplus, the private sector goes into deficit. If the government reduces its debt, everyone else has to go into debt in exactly that proportion in order to balance their own budgets.”

Perhaps the best practical example of this is university tuition fees. To reduce public sector spending, the government stopped subsidising university fees. Accordingly, university tuition fees increased and the private sector took on the extra costs. The reduction in the public sector’s spending burden translated into a direct increase in the spending burden of the private sector; and consequently the private sector was forced to take on more debt.

It should be noted that Graeber makes no mention of the external sector. The government could run a surplus and so could the private sector, but only if the external sector runs a deficit. For the external sector to run a deficit we would need to start exporting far more goods and services than we import. That is Britain would need to become a net exporting nation, like Germany or Japan. Since we are a long way off from being a net exporting nation, the British economy would require a massive structural transformation for this to be a possibility, Graeber most likely has intentionally neglected to mention it.

Sectoral Balances and Money Creation

People, who are unfamiliar with sectoral balances may be questioning this logic. You may be thinking to yourself, “But why does anybody have to be in debt? Everyone lives within their means and nobody ends up owing anything. Why can’t we just do that?”

In response, Graeber aptly suggests:

“Well there’s an answer to that too: then there wouldn’t be any money. This is another thing everybody knows but no one really wants to talk about. Money is debt. Banknotes are just so many circulating IOUs. (If you don’t believe me, look at any banknote in your pocket. It says: “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of five pounds.” See? It’s an IOU.) Pounds are either circulating government debt, or they’re created by banks by making loans. That’s where money comes from. Obviously if nobody took out any loans at all, there wouldn’t be any money. The economy would collapse.”

This is a point that Positive Money has repeatedly made. Under the current monetary system, for there to be any money in the economy there has to be an equal amount of debt. Accordingly, this debt has to be owed to someone, and usually tends to be the wealthiest cadres of society. Indeed, this is why more money in the economy (or higher levels of debt) tends to lead to inequality. Because virtually all money is created by banks someone must pay interest on nearly every pound in the UK. The bottom 90% of the UK pays more interest to banks than they ever receive from them, which results in a redistribution of income from the bottom 90% of the population to the top 10%.

Therefore if a government decides to run a surplus, and forces the private sector to take on more debt, the government implicitly exacerbates inequality:

“If the government runs up a lot of debt, that means rich people hold a lot of government bonds, which pay quite low rates of interest; the government taxes you to pay them off. If the government pays off its debt, what it’s basically doing is transferring that debt directly to you, as mortgage debt, credit card debt, payday loans, and so on. Of course the money is still owed to the same rich people. But now those rich people can collect much higher rates of interest.”

Fiscal Policy and Financial Crises

Next, Graeber suggests that running a government surplus can lead to unsustainable levels of private sector debt, which ultimately leads to crisis.

“But if you push all the debt on to those least able to pay, something does eventually have to give. There were three times in recent decades when the government ran a surplus… each surplus is followed, within a certain number of years, by an equal and opposite recession.”

Of course this logic is accurate, but only to a certain extent. On the one hand, the statistics do suggest that the most recent attempts at running a budget surplus did eventually result in a crash. However, this does not imply that if the government ran a deficit there would not have been a crisis. In the run up to a number of a crises, including the most recent, the government also ran a budget deficit. Therefore, crises can erupt when the government runs either a surplus or a deficit.

Public sector finances alone cannot explain the complex workings of modern-day economies. We also have to look at private sector spending and debt (as well as that of the external sector). Indeed, the majority of UK crises have been preceded by a significant expansion of private sector borrowing from banks. Borrowing from banks in itself is not bad for the economy, as long as borrowing increases the productive capacity of the economy and leads to an increase in incomes, so that outstanding debts can be paid off.

However, when borrowing is used to buy pre-existing assets in the property and financial sectors it increases the level of private debt but does not lead directly to an increase in incomes. When the level of private debt increases while the earning capacity of the economy (private sector incomes) remains unchanged, the economy becomes more susceptible to shocks, as people do not have enough income to pay off their outstanding debt.

Graeber suggests that this type of unproductive borrowing can be expected in the future:

“There’s every reason to believe that’s exactly what’s about to happen now. At the moment, Conservative policy is to create a housing bubble. Inflated housing prices create a boom in construction and that makes it look as if the economy is growing. But it can only be paid for by saddling homeowners with more and more mortgage debt.”

Graeber is correct in suggesting that we should be worried about the housing bubble and the over-accumulation of private sector debt. It needs to be stated, however, that the housing bubble and the vast accumulation of private sector debt was also taking place whilst the Labour government ran relatively large successive deficits.

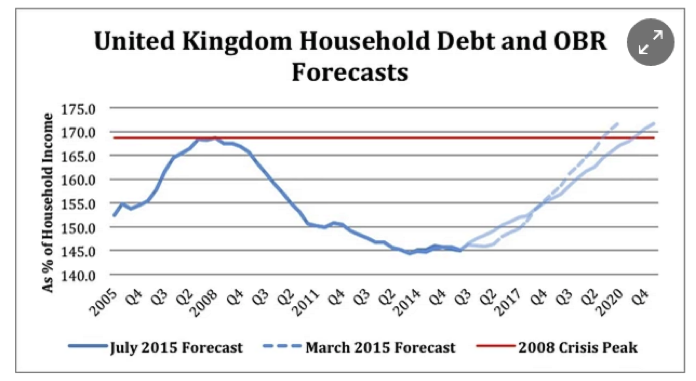

This is not to suggest that governments should ignore the potential dangers of running a budget surplus. Currently, by aiming to balance the budget the government is forcing more debt on younger generations, working households with incomes below £30,000, and the self-employed. Most of this debt is being forced on groups before they can even apply for a mortgage. Which either means they will not be able to afford a mortgage, or that they will already be highly leveraged when taking on another loan to buy a house. The latter seems to be the case, as the OBR predicts that household debt is going to skyrocket over the next five years.

Monetary Policy to Compliment Fiscal Policy

Clearly, fiscal policy, regardless of what guise it takes, can lead to economic crises. Policy makers need to be aware of how fiscal policy influences the private sector, and the accumulation of private sector debt. Fuelling economic growth by increasing the private sector debt burden often results asset bubbles and ensuing crises. Accordingly, fiscal policy needs to be accompanied by a number of other policy measures, including appropriate monetary policy.

Policy makers would benefit by adding Sovereign Money Creation (a form of People’s QE) to their monetary policy toolkit. Allowing central banks to create money for the real economy would stimulate people’s incomes without a corresponding increase in the balance of public or private debt. In effect, the public sector would not have to be so reliant on increased levels of private debt to fuel growth.

In this sense, monetary-financing for the real economy could be an additional instrument added to the central bank’s ‘toolbox’. This is not to suggest that monetary-financing would be used for funding government deficits, rather it could be another macro-economic tool at the central bank’s disposal to help manage the economy.

Moreover, with Sovereign Money Creation the ratio of debt to income could be lowered, as increased spending would take place without governments increasing their budget deficits and without the private sector increasing levels of borrowing. Lower debt-to-income ratios would make our financial system more resilient to potential shocks, as outstanding loans would be easier to service. Finally, central banks would also be better equipped to deal with such shocks if they were permitted to create money for the real economy.