Overt Monetary Financing – dangerous drug or miracle medicine? (Lord Adair Turner)

On 7th September 2015 Positive Money hosted an event “ Making Money Work: can innovations in monetary policy promote long-term prosperity?”, with Lord Adair Turner, former Chairman of the Financial Services Authority, and now Chairman of the Institute for New Economic Thinking. Lord Turner gave a talk on how the monetary system works, the dangers of debt-fuelled growth and monetary financing as a new monetary policy tool that should be considered by governments and central banks. Here’s a script of his speech [emphasis added]:

It’s a pleasure to speak at an event organised by Positive Money, an organisation which has rightly focused attention on a fundamental issue of macroeconomic theory and policy – the inherent nature and function of money, and the mechanisms by which purchasing power is created within our economy. I do not in fact agree with the radical policy change which Positive Money proposes – the abolition of fractional reserve banks and a move to 100% reserve banking.

[Our note: 100% reserve banking is not an entirely exact description of Positive Money’s proposal; in Sovereign Money system there would be no reserves – please see more on the differences between 100% reserve versus Sovereign Money system here.]

But I believe that it is impossible to understand why the 2008 crisis occurred, and even more, why the recovery from the crisis has been so slow and difficult, without focusing on the issues which you have raised.

The root cause of crisis and weak recovery

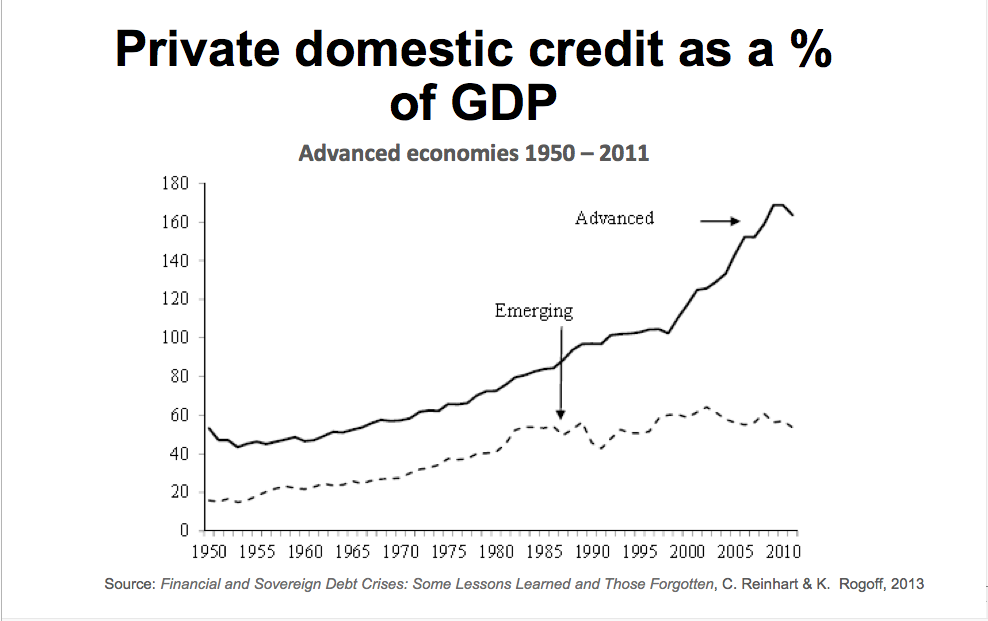

The fundamental reason why the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis has been so slow and difficult, can be summed up on Slide 1 which shows private credit as percent of GDP in advanced economies rising relentlessly from 50% in 1950 to 170% by 2008:

That rising leverage, focused on real estate purchase, left many households and corporates severely overleveraged when confidence broke and property prices fell . That then unleashed a wave of attempted private sector deleveraging which depressed nominal demand and drove economies into recession. And that in turn created an environment in which debt does not actually go away but simply shifts from private to public sector:

With large public deficits the inevitable consequence of recession and slow growth, and indeed necessary to sustain growth

But with the resulting increase in public sector debt as percent of GDP seeming in turn to require public debt consolidation and austerity

Austerity however, which in turn has a depressing economic effect

That is I believe the essence of what has occurred: and it is a pattern which should have been familiar from the Japanese experience after 1990, well documented by Richard Koo in his book The Holy Grail of macro economics, and captured by his concept of a “balance sheet recession”. And it is the pattern which has been repeated in the US, the UK and multiple other countries since 2008, as well described for the US by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi in their important book House of Debt. So too much private debt, too high a level of leverage, and post crisis debt overhang can play havoc the macro economy.

Pre crisis orthodoxy and the financial veil

But it is striking that pre-crisis economic orthodoxy largely ignored the growth of private leverage or assumed that it was benign.

Finance theory told us why we need debt contracts as well as equity contracts in order to support capital investment, but largely ignored the question of whether we could have too much debt as well as to little.

Macroeconomic theory and central bank policy practice, gravitated to the assumption that as long as inflation was low and stable, macroeconomic stability was assumed, and that the details of the financial system and of financial and real economy balance sheets could be safely ignored- the financial system a mere “ veil “ through which interest rates passed to the real economy but of no great importance in itself.

In retrospect that was huge intellectual mistake. And at its core were wrong assumptions about the role of banks and of credit creation, assumptions which Positive Money has rightly challenged.

What banks actually do

Pick up almost any undergraduate economic textbook, and if it describes the banking system at all it will say something like “Banks take money from depositors and lend it to businesses/entrepreneurs, thus allocating savings between alternative capital investment projects”. But as a description of what fractional reserve banks do in advanced economies this is almost entirely mythical. First because banks do not just take pre-existing money and lend it on: they create credit (bank assets) and matching money or other bank liabilities, which did not previously exist: and by maturity transformation (with loans of longer maturity than their deposits) they create new purchasing power in the economy. That reality was considered crucial by early 20th-century economists such as Knut Wicksell, Friedrich von Hayek, John Maynard Keynes (particularly in the Treatise on Money,) Irving Fisher and Henry Simons – but from about the 1960s onwards it largely disappeared from mainstream orthodox economics. And that was dangerous, because if banks can create purchasing power, it matters a lot how much they create and to whom that purchasing power is allocated. Obviously if they create too much purchasing power they might produce harmfully high inflation – a danger on which Wicksell focussed much attention. But in the years running up to the crisis of 2008, we had low and stable inflation – so that seemed to justify the assumption that whatever the level of leverage in the economy, it must be broadly optimal. And that in turn might have been a reasonable assumption if all credit was indeed extended for the purpose which undergraduate textbooks assume – to fund new capital investment. But that part of the orthodox description also turns out to be completely wrong. For most bank credit in advanced economies – some 85% or so – is not extended to finance new capital investment, but funds either increased consumption or, to an even greater extent, the purchase of assets which already exist – and above all existing real estate. And the most fundamental cause of financial and macroeconomic instability in modern economies, is the interface between the infinite capacity of unconstrained banks to create credit, money (or money equivalents) and purchasing power, and the inevitably inelastic supply of real estate, and of the locationally specific land on which it sits. As a result inflation targeting is insufficient to ensure financial and macroeconomic instability, and public policy instead must seek to constrain, manage or influence both the total quantity of private credit created (and thus the leverage which results ) and its allocation between alternative uses. But is that a sufficient response, or should we do something more radical?

The radical option – abolishing fractional reserve banks

Many of the economists who observed the havoc caused by private credit creation and subsequent deleveraging in the 1920s and 1930s, believed that a far more radical solution was required. As Henry Simons saw it, it was inevitable that “in the very nature of the system, banks will flood the economy with money substitutes during booms and perpetuate futile efforts at general liquidation thereafter” and in the Chicago Plan he, Irving Fisher and others therefore proposed that fractional reserve banks should be abolished, and that all private banks should operate with 100% reserves and should not be allowed to lend money. Milton Friedman also argued the same in an article in 1948. Which is very striking, because all of those three economists – Fisher, Simons and Friedman- were in all other respects extreme free-market liberals, strongly committed to the idea that government should keep out of business activity and that capitalist competition was the only way to economic success. Essentially indeed, what Simons in particular believed was that by extending free market principles to banks which can create money, we had made a category error, since banks which create money are not at all comparable to manufacturers who create cars, or to restaurants who provide meals, or to any other sector of the economy. So should we abolish fractional reserve banks and instead move to 100% reserve banks – in which banks hold at the central bank (or in notes and coins in their vaults) reserves equal to the deposits placed with them, and in which therefore banks would be unable to create money and purchasing power, because the monetary base of government fiat money and the money supply will always be exactly the same thing? Well I’m not convinced that we should, and in my new book I set out why I draw back from that really radical proposal. Essentially I believe:

First that there are insuperable transitional difficulties in moving from a system in which large fractional reserve banks and large quantities of private credit and leverage already exist

But second and more fundamentally, that an optimal system does entail some role for the creation by purchasing power by private sector banks, rather than by state fiat money creation, with the allocation of that purchasing power subject to free market disciplines

But while I do not therefore endorse the extreme radicalism of Fisher, Simons, early Milton Friedman and Positive Money, I think their proposals are based on insights which should inform our actual policy choices. And while I think we should continue to have fractional reserve banks, I think the fraction should be much larger than it is today, with far higher bank capital requirements, with central banks imposing formal reserve requirements which constrain the banking multiplier, and with a deliberate policy objective of achieving a less leveraged real economy.

Sources of nominal demand growth

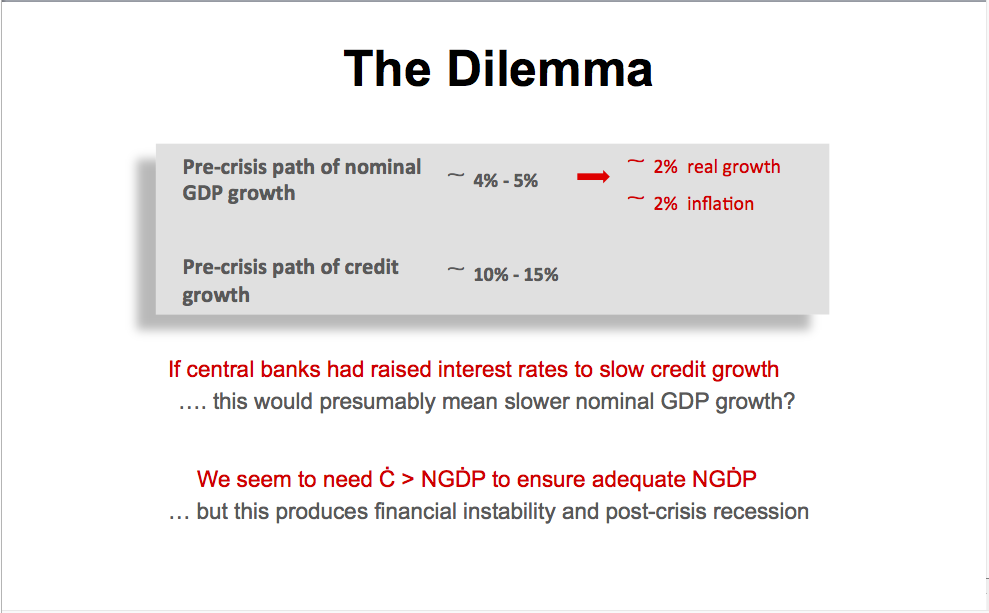

But that of course raises a question – how in such a system to achieve adequate nominal demand growth? Before the crisis we relied essentially on private credit creation, and on average over time advanced economies displayed the pattern shown on Slide 2:

With nominal GDP growing at around 5% per annum, a pace broadly consistent with trend real growth and inflation of about 2%

But with nominal credit growing at around 15% per annum, so that leverage relentlessly increased

And with that pace of increase in credit appearing essential in order to achieve adequate nominal demand growth

But clearly such a pattern cannot be stable in the long term, for if we truly need 15% credit growth to achieve 5% nominal demand growth, we will eventually produce crisis and post-crisis debt overhang. So is there a more stable and sustainable way to stimulate nominal demand growth? The mid-20th-century radicals believed that there was, and their answer was indeed the only possible one given that they had also proposed 100% reserve banks. For if private banks cannot create credit, money and purchasing power, then nominal demand will only grow if central banks and governments together create sovereign fiat money and use it to finance fiscal deficits. And conversely, in such a system, if governments and central banks see a need to slow the economy down, the only way they can do so is to run fiscal surpluses and withdraw money from circulation. Thus as Friedman put it, the logical and, he believed, desirable corollary of 100% reserve banks is a system in which “the chief function of the monetary authority [would-be] the creation of money to meet government deficits or the retirement of money when the government has a surplus” and “government expenditures would be financed entirely by tax revenues or the creation of money” and not at all by the issue of interest-bearing debt. And again what is striking is not just the radicalism of this proposal, but who proposed it. For Simons, Fisher and Friedman in 1948 were strong believers in sound money and low inflation, but believed that the overt monetary finance of fiscal deficits was completely compatible with that. So should we accept the second half of the radicalism of those mid-20th-century economists – the idea that governments and central banks together should, when the conditions are appropriate, use money financed fiscal deficits as a means (or even the primary means) to stimulate aggregate nominal demand? To answer that question, I think it vital to distinguish between two considerations:

First whether overt and permanent monetary finance is technically feasible and whether in some circumstances it is desirable

And second whether the political economy risks of the misuse of overt monetary finance can be contained

Overt Money Finance is undoubtedly technically feasible and desirable in some circumstances

In technical terms there are no reasons whatsoever which make overt money finance (OMF) unfeasible, no reasons why it must lead to excessive inflation, and there undoubtedly exist circumstances in which it would be the optimal policy. The technical feasibility of OMF, and the fact that it need not lead to excessive inflation, is most easily understood if we think in terms of a world without fractional reserve banks, in which all money is either paper money or electronic money held at 100% reserve banks, and in which therefore the increase in the money supply is precisely determined by the quantity of new money which the central bank and government together create. And it is intuitively obvious in that environment that the impact of OMF on aggregate nominal demand will depend wholly and straightforwardly on the amount of new money created. If the central bank and government together arrange monetary finance of a small fiscal deficit (say 1% of GDP), a relatively slow growth of aggregate nominal demand will result: but if they finance with money a much larger fiscal deficit, a far more rapid growth in aggregate nominal demand will result and in all likelihood excessive inflation. Thus in the 18th century, the Pennsylvania Colony successfully used printed paper money to stimulate nominal demand and economic growth without excessive inflation, but that success, as Adam Smith commented, depended crucially on the moderation with which the expedient was used. Other colonies used the tool to excess, and as a result, as Smith observed, “for want of this moderation… produced much more disorder than conveniency”. The impact depends crucially on the quantity of money created.

OMF with fractional reserve banks

With fractional reserve banks, and thus a money supply which is a multiple of the monetary base, things are clearly more complicated, but the same fundamental conclusion still remains robust – the impact of OMF will depend crucially on the quantity of the operation, and central banks have the tools to ensure that the impact on aggregate monetary demand is appropriately moderate rather than excessive. The technical arguments are complex, and I do not have time this afternoon to go through them all, which of course has the advantage that you will have to buy my book to consider them in detail. But let me just make three points:

First as Willem Buiter has proved in a formal mathematical paper, monetary finance of a fiscal deficit – and the resulting creation of irredeemable fiat non-interest bearing money – is bound in all circumstances to stimulate aggregate nominal demand; and that means that any assertion that central banks and governments can “run out of ammunition” to stimulate nominal demand is simply wrong. Whether or not we face a demand driven risk of “secular stagnation” can be debated – but as Buiter puts it, if that risk ever became reality, that would be a policy choice not an unavoidable necessity.

Second, any danger that the initial stimulus of small OMF operations will be subsequently and harmfully magnified by the operation of the banking multiplier – with banks at a later date creating credit, money and purchasing power as a multiple of the additional monetary base created – can be offset by the imposition of quantitative reserve requirements.

Third, contrary to what some critics have argued, effective OMF operations do not leave central banks committed to maintain zero interest rates in perpetuity. Obviously to be effective they imply the creation of new monetary base which is non-interest-bearing, and this implies that some part of commercial bank reserves at the central bank should be non-remunerated. But it is quite possible for a central bank to pay zero interest on a part of central bank reserves, while using remuneration of reserves above that tier as one among the tools available to set market interest rates appropriately so as to achieve inflation targets. Indeed one of the arguments for favouring OMF over some alternative mechanisms to stimulate nominal demand is that it could allow for a faster return to more normal interest rates.

There are indeed, I now strongly believe, no technical reasons whatsoever why OMF cannot be used to stimulate aggregate demand, and no technical reason why the extent of that stimulus should not be calibrated to an appropriate level. And all of the supposed arguments of technical impossibility which I have encountered dissolve on closer inspection. If therefore there exist circumstances in which it is desirable to stimulate nominal demand, and if we focus solely on the technical arguments, OMF should be among the options considered.

OMF as a policy option if and when nominal demand is deficient

Now of course it could be that no nominal demand stimulus is appropriate or needed. Some economists of the German ordo-liberal school indeed come close to asserting that it will never be required, arguing that there is nothing wrong with mild price deflation – so that an economy could function quite well without any nominal demand growth, combining, for instance, real growth of 2% with price inflation of -2%. But the strong consensus across the world, as reflected in central bank inflation targets of around plus 2%, (and this is part of the pre-crisis consensus with which I do agree), is that modern economies work best if on average over time nominal demand tends to grow at around 4 to 5% per annum, allowing a combination of moderate real growth and low but positive inflation. And the common assumption behind all the policy propositions debated and implemented after 2008 was that we faced a deficiency of nominal demand and that by one means or other we needed to stimulate it. The QE programs of the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and the ECB were all justified on the grounds that nominal demand was insufficient to achieve inflation targets: and the alternative arguments for still larger debt financed fiscal deficits, put forward by for instance Paul Krugman or Larry Summers, were likewise predicated on a belief that aggregate nominal demand was deficient.

If aggregate nominal demand was not deficient we should not have implemented close to zero interest rates and QE, nor allowed fiscal deficits to grow as much as they did

And if, as almost everyone agreed, it was deficient, OMF was a technically feasible option which could have been considered alongside ultra-loose monetary policy or debt financed deficits

Moreover, and again from a purely technical point of view, there are strong arguments that in some circumstances OMF could be superior to the other two options, because more likely to be effective and/or less dangerous:

Compared with debt financed fiscal deficits, OMF may be more effective because it does not leave us struggling with the question of what to do about future public debt burdens, nor create the danger that the anticipation of those future debt burdens will induce a Ricardian equivalent offset to nominal demand stimulus today

And compared to ultra-loose monetary policy and QE, it may be both more effective and less risky.

More effective because the transmission mechanism is more direct, injecting new demand, as Friedman put it, directly “into the current income stream”, rather than relying on the indirect transmission mechanisms of QE, by which higher asset prices are meant to induce increased investment or consumption by wealthier companies or individuals.

And less risky because the sustained ultralow interest rates to which a purely monetary policy commits us, may well produce dangerous financial engineering operations long before they stimulate the real economy, and because ultra-loose monetary policy can only ultimately work by re-stimulating the very growth of private credit which first got us into this mess in the first place

Overall therefore, I have become convinced that the technical arguments for treating OMF as an available policy option are incontrovertible.

The valid political economy counter argument

But it is striking how difficult it is to persuade even many fine economists of that reality. And that, I have come to believe, reflects the fact that many people do not want to believe that OMF is technically feasible and for a very good reason. For once we accept that OMF is technically feasible and potentially desirable, we break the taboo against its use, and as a result then face severe political economy risks. For while it is undoubtedly possible to use overt permanent money finance of fiscal deficits in appropriately moderate amounts to avoid deflation and stimulate the economy, as for instance Japanese finance minister Takahashi Korekiyo illustrated in the 1930s, it is also obviously possible to print money in excess – producing the hyperinflation of Weimar Germany or modern day Zimbabwe. For once it is clear that OMF is technically feasible, why will politicians subject to short-term electoral pressures and the demands of their constituencies not use it to excess? So the crucial issue with OMF is not actually the technical feasibility, but the political economy of its use. And the crucial question is whether we can construct credible constraints of rules and institutional responsibilities, which will ensure that politicians do not create money and purchasing power in excessive quantities, nor allocate the new purchasing power created in inefficient and politically biased ways. In principle, it should be possible to construct such constraints, and the most obvious way to achieve that might be to build on the system of central bank independence and of explicit inflation targets. We could, for instance, give to the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England the authority to determine what quantity of overt money finance would be compatible with achieving the inflation target: and an MPC equipped with such a authority might well in 2009 have determined that, for instance, £35 billion of overt and permanent money finance of increased fiscal expenditure might have been a more effective mechanism to stimulate aggregate nominal demand than £375 billion of supposedly temporary QE. Other mechanisms might also be possible. But the essential point is clear: the key issues here are political, not technical. And we should only take OMF out of the taboo box, and use it to stimulate aggregate demand, if we are confident that we have a robust mechanism to prevent its misuse. And those mechanisms must be based on rules and clearly defined independent authorities: broad promises to only do a sensible amount, or to cut off the taps once full employment is achieved, would not be sufficient. Equally however, we should recognise that if we do leave OMF in the taboo box, that also creates severe dangers – because it leaves us relying on private credit growth to ensure adequate nominal demand, with ultralow interest rates and QE used to stimulate that credit growth. We have essentially two mechanisms by which to ensure growth in aggregate nominal demand

States can create nominal demand via fiscal stimulus funded with fiat money creation

And fractional reserve banks can create nominal demand via maturity transformation

But both mechanisms are potentially very dangerous.

States, subject to political pressures, may create too much money or allocate it badly.

And the private banking sector, if unconstrained by public policy, may create too much private credit and leveraged, and allocate that private credit badly – as they did before the 2008 crisis.

We face a balance of dangers, not perfection on one side and inevitable perdition on the other. States fail and markets fail, and optimal policy requires us to strike a balance. I believe that before the crisis we were far, far too relaxed about private credit and money creation, and that in the aftermath of the crisis we have been too terrified of the potential role of constrained and moderate OMF. But there are severe risks on either side; which is why my book – if I may conclude with a shameless piece of advertising – is entitled “Between Debt and the Devil”*. We’ll publish a video from the Making Money Work event shortly, watch this space. *The book will be launched at the LSE event on October 21st, 6.30 – 8.00, with Lord Turner and Robert Peston in conversation about the arguments.