George Osborne’s Permanent Bank Levy – Is it Seigniorage?

Positive Money (PM) is not impressed by the Chancellors’ attempts to impose some kind of payback on the banks for the damage they have caused to the Economy since 2008. “In fact, bar a one-off punitive tax on bankers’ bonuses and a bank levy, little has changed” says a PM report ‘Banking vs Democracy 2012’. I’d like to make the case that while the Bank Levy, introduced in 2010 is indeed rather puny, it establishes a very important principle – that the banks should pay something for the money that they create.

The “Permanent Bank Levy” was introduced in George Osborne’s June 2010 Emergency Budget, having been negotiated as part of the Coalition Agreement. (Osborne has been in the habit of tacking ‘permanent’ on to the name, in part to distinguish it from Labour’s 2009 one-off levy on bankers’ bonuses). In his budget speech he declared the aim of the Bank Levy “is to incentivise a reduction in the use of wholesale finance by banks, with a view to reducing the risk of another financial crisis being triggered by liquidity issues”. The Bank Levy was to be “based on total liabilities and equity as shown in the relevant balance sheet” of the 30 or 40 biggest banks. The initial rate was set at 0.05% and was expected to raise “in excess of £2bn.”

But what possessed Osborne the Tory Chancellor to agree with his Coalition partners that a Bank Levy was the necessary and right thing to do? The short answer is that the IMF told them so. In a report (1) produced in 2010 for the G20 Summit of world leaders, the IMF rejected the widely publicised tax based on financial transactions — the so-called ‘Robin Hood’ tax. Instead they proposed that banks should pay a ‘Financial Stability Contribution’ (FSC).

“The main component of the FSC would be a levy to pay for the fiscal cost of any future government support to the sector. This could either accumulate in a fund to facilitate the resolution of weak institutions or be paid into general revenue. The FSC would be paid by all financial institutions, initially levied at a flat rate (varying though by type of financial institutions) but refined thereafter to reflect individual institutions’ riskiness and contributions to systemic risk—such as those related to size, interconnectedness and substitutability—and variations in overall risk over time.”

So the word ‘levy’ was introduced into the discourse by the IMF, not as a simple tax, but the basis for a fund to offset future risk. Clearly the size of the risk posed by each banking institution depends on the amount of funds at their disposal, but also the riskiness (or recklessness!) of the loans or investments they have made.

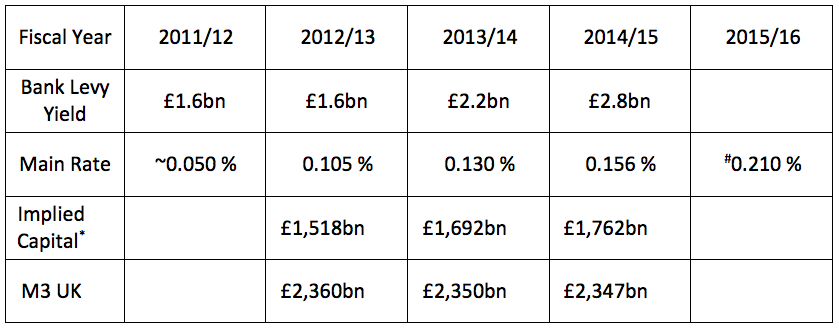

Osborne picked up on the IMF’s idea, not as the basis for a stabilisation fund but as a straightforward Tax. The balance sheet items of the 30 or 40 largest financial institutions were to be the basis for the levy. The least risky items on the balance sheets were to be exempt for tax. Tax at half the main would apply to moderately risky items, then the full Main Rate of the tax was to be levied on the rest. Thus the IMF’s ‘financial stability contribution’, became Osborne’s ‘permanent’ Bank Levy. Here’s how the Levy worked during the Coalition Government’s term of 2010-15:

TABLE 1: BANK LEVY YIELD, RATES AND IMPLIED TAXABLE CAPITAL

The Bank Levy was introduced from 1 January 2011. Payments began to be received from 2011-12 onwards.

M3 is an economists’ measure of the total amount of money in the economy. Most of M3 (97%) is to be found on the balance sheets of the banking institutions, having been created electronically within the banks themselves. The remaining 3% is M0, tangible cash in the form of banknotes

*Implied Capital is the Bank Levy yield divided by the Main Rate. Only part of the large banks’ balance sheets is taxed at the Main Rate. Low-risk items are exempt, and medium risk items are taxed at one-half of the Main Rate.

~ The rate was initially proposed at 0.04%, finalised at 0.05%, then increased for the last two months of Fiscal 11/12 to 0.10%. Hence no calculation of Implied Capital was made for 11/12

# Proposed as the final rate, but in the June 2015 Emergency Budget lower rates were introduced.

So the Bank Levy has collected small but useful amounts from the larger financial institutions, but usually fell short of its target expected yield, and never reached the £3.6bn achieved by the previous government’s Bankers’ Bonus Tax. Nor was it a big part of the total amount paid in taxes – £21.7bn in 2012/13 – paid by the banks (2).

The rate of the Bank Levy tax was, as intended and signalled, gradually stepped up, but the rate has been changed, sometimes without warning — for example in March/April 2011when it was increased from 0.05% to 0.10% for two months. It was due to reach its final ultimate rate of 0.21% in 2015/16. But then in the emergency June 2015 Budget, Osborne gave in to the pleas of the big banks, especially HSBC and Standard Chartered. A timetable of reductions of Bank Levy from 0.21% was announced with the rate to settle down at 0.10% by January 2021.

Osborne’s permanent Bank Levy – it’s Seigniorage!

The Bank Levy is a brand new form of tax. Despite it being attacked by the greatest powers in the land, the big banks, it has survived. Just as importantly the operating procedures for the bank levy have been established, definitions have been thrashed out and agreed. This is a tax which works, and continues to be paid.

But the bank tax is also important because it embodies an important if unstated principle: that banks should pay back to society some kind of recompense based on the amount of money that that they create. The technical name for this is seigniorage. What the analysts at the IMF had pushed for and what Osborne’s Bank Levy represents is a straightforward example of seigniorage in action. It is far from a new idea, and a form of it already exists right here in the UK.

Seigniorage from the Bank of England (BoE): Profit from issuing banknotes.

Seigniorage may be an unfamiliar word, but a simple idea. In the old days when the sovereign (the king) issued new money, he benefitted thereby. This still happens when the Bank of England issues banknotes and coins. It does indeed reap a financial reward – seigniorage – which is paid over annually to Her Majesty’s Treasury. Here’s how it works:

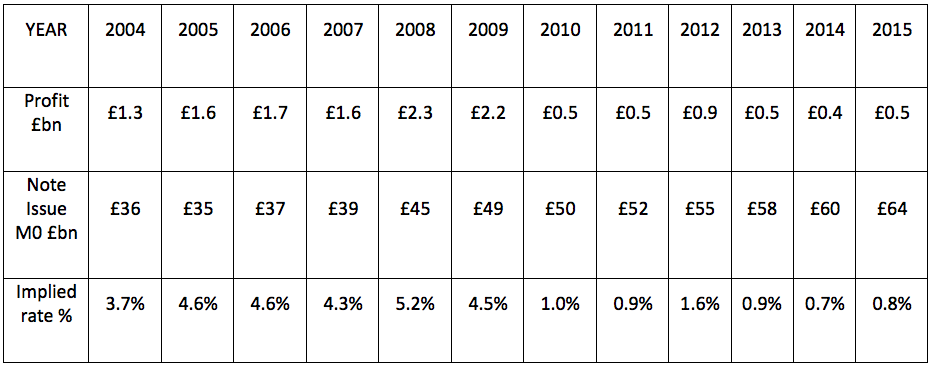

New banknotes are being issued all the time by the Bank of England (BoE). In the period 2014-15, for example, an additional £3.6bn worth of banknotes were put into circulation by the BoE. So, was a cheque for £3.6bn handed over to HM Treasury by the Bank? No. A more mysterious method to calculate seigniorage is used, although the BoE doesn’t actually use the word. They prefer to call it “Profit on note-issue”.

In essence (3), to calculate the Profit on note-issue, the BoE uses the Total value of the banknotes circulating in the economy. This is what economists call M0. In 2015 banknotes with a face-value of £64bn were circulating in the UK economy. (There are banknotes issued by Scottish and Northern Ireland banks, too, but under BoE supervision. Part of the seigniorage is remitted to Scottish and Northern Ireland governments.)

The formula for ‘Profit on Issue of banknotes’ (Seigniorage) can be taken as:

Total Value of banknotes in circulation ‘M0’ multiplied by the Average Bank Rate during that year.

Here’s what the BoE has paid over to HM Treasury for the last 12 years. Although the total note-issue has nearly doubled in that time, the seigniorage or Profit on banknote Issue has shrivelled to less than a quarter of its peak in 2008. This reflects the BoE policy of rock-bottom interest rates since then.

TABLE 2: SEIGNIORAGE — PROFIT ON ISSUE OF BANKNOTES BY BoE

So a form of Seigniorage exists and is practiced by the Bank of England in relation to the issue of banknotes and coins – M0 in economists’ parlance. In a recent paper for the World Economics Association Martin Knibbe (4) describes this as ‘public seigniorage’. He explains that the (central) Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank act in a similar fashion, and also pay over to their respective governments the profit on note-issue, as do most other central banks.

Private Seigniorage too?

Should the same principle be applied to ALL of our money, including that created by private banks? Knibbe describes this as “private seigniorage” to distinguish from the public seigniorage derived from note-issue. In a small way this is just what Osborne’s Bank Levy does — it charges banks for their privileged creation of nearly all of M3. The Levy is based on banks’ balance sheets, which is another way of saying how much money the bank owed or owned to or by its customers. Most of this money on banks’ balance sheets has been created by the banks themselves in the ordinary processes of making loans. (as PM and others have explained ad nauseam, but which still seems to baffle mainstream economists and media economics correspondents!)

In 2014-15 the main Bank Levy was set at 0.156%. So should it have been set at 0.8%, i.e. the same rate as the existing ‘public seigniorage’? If so then Osborne and the Treasury would have collected more than five times as much in taxes – £14bn rather than the £2.8bn actually achieved.

Remember too, that interest rates are being pinned down artificially while the bank-induced crisis of 2008 continues. Back in the ‘normal’ times pre-2008 a bank rate of 4.6% would have been seen as very reasonable. If this rate was used for the Bank Levy it would, in theory, result in tax revenues of £81bn, a very sizable sum indeed, which would cover about 10% of all government expenditure. [Knibbe does a similar calculation for the Euro-zone and calculates that a sum of €300bn in private seigniorage, or €1,000 per citizen could be claimed from the financial institutions for their ‘exorbitant privilege’ of creating our money.]

This sounds like a huge and insupportable burden to impose on the banks. The profits of the big five banks in 2014 were just one-quarter of this at £20bn. Even bankers’ bonuses are a about a half of this at £42bn. (5) But these are not normal times for the banks. Before the Crash of 2008 their profits were many times more than this. Perhaps the figure of £80bn would indeed be equivalent to the banks’ benefit of printing their own money?

But the Bank Levy was designed to be a financial stabilisation mechanism. It was always intended to reduce balance sheets bloated by risky and reckless bank lending. If the proper rates of Bank Levy tax were applied, then the banks appetite for such risky lending via profligate money-creation would be severely blunted. A sharp incentive would exist for banks to create and lend less money.

This entirely benign result could well see the economy suffering from lack of liquidity, where insufficient money is flowing around the system to keep the economy moving. At that point the opportunity for the BoE to inject new money into the economy via QE is the obvious answer. But this time it must be different, with QE being used in a productive way which helps each and every citizen, not just to bail out the banks.

Is this achieving Positive Money’s Agenda?

But would a full-rate Bank Levy which leads to productive QE go any way towards fulfilling Positive Money’s proposals for reform of the whole money system? From the proposals page, these are

Take the power to create money away from the banks, and return it to a democratic transparent and accountable process.

Create money free of debt.

Put new money into the real economy rather than financial markets and property bubbles.

The Bank Levy even at a low rate would result in Proposal 1 being partially fulfilled. Money would still be created in the banking sector, but has to be paid for. The higher the rate, the less appetite the banks would have for creating money through lending. This in turn opens up the possibility for publicly created QE money. This is politically feasible because the principle of bank levy has been conceded, the details have been thrashed out, the tax authorities have the systems in place, and expanding on it requires no new legislation. Expect huge resistance, and even underhanded dealing by the private banks to these proposals! But a determined government which lays out publically the realities money creation by the private banks could surely carry public opinion on this. Positive Money has a hugely important role in changing both public perceptions and updating economic theory which still hides behind the discredited ‘loanable funds’ theory of lending.

Since the banking crash of 2008 two important principles have been established, which formerly would have been rejected as ‘unthinkable’ or ‘impossible‘.

QE makes it quite apparent that the BoE as the agent of our Government can and does create new electronic money and inject into the economy in an appropriate way.

With the Bank Levy the principle that private banks should pay ‘rent’ for the money they create has also been established, and by implication that they create our money with our permission.

So the main elements of Positive Money’s proposals are now in place without any further legislation. What remains is to implement these powers for the benefit of the many, initially by increasing Bank Levy to the same rate as banknote profit. The introduction of a regular programme of QE would follow. The opportunity would then be clear to make QE work for the benefit of the economy.

Postscript: In his emergency Budget in July 2015 Osborne announced changes to the Bank Levy, and other bank taxes:

“The annual levy banks pay on their balance sheets is to be reduced gradually but an 8% surcharge on their profits will be introduced.”

The Treasury said the bank levy would be cut from its current 0.21% to 0.1% in 2021, by which time it would apply to banks’ UK balance sheets only.

HSBC said earlier this year that the bank levy was a factor in whether to move its headquarters from the UK.”

Note that the profit surcharge will be levied on all banks including the smaller ‘challenger’ banks which were intended to introduce a bit of competition for the ‘too-big-to-fail’ banks.

—————————–

References

Numbers and quotes have been taken from Bank of England statistical publications as well as HM Treasury.

A Fair and Substantial Contribution by the Financial Sector – Final report for the G-20 (Prepared by the Staff of the International Monetary Fund – July 2010)

Seely, Anthony (27May 2014) Taxation of Banking Standard Note SN 5251 House of Commons Library

This is a very useful report which identifies much of the politics around the introduction of the Bank Levy. The figure for total tax payments comes from HM Revenue & Customs. They estimate that tax receipts as a whole from the bank sector – that is, PAYE, corporation tax and the bank levy – added up to £21.7bn in 2012/13.

I say ‘in essence’ because the stated procedure of the BoE involves hypothetical Bonds which pay interest. I explain how I think this works in Boyle (2007) Seigniorage and the BoE: A deeper mystery Prosperity Glasgow which can be found here.

Knibbe, Merijn Private seigniorage, defined and estimated (includes a free Eurozone example!) Real World Economics Review 71, Sept 2015