Bank of England’s chief economist hints towards a digital form of central bank money to compete with bank-issued money

Last week Andrew Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist hinted that current monetary policy might be broken, and that other policies might be needed. He briefly hinted that one policy might involve the central bank issuing a form of digital cash that would end up competing with the bank deposits issued by commercial banks (and which make up 97% of all the money we use).

The Problem of the Zero Lower Bound

The pretext for Haldane’s speech was the problem of low interest rates. The problem since the crisis has been that you can only lower interest rates so far. In an economy that is already over-indebted, even interest rates of 0.5% are unlikely to be low enough to encourage people to take out further debt. If people don’t want to borrow, then banks won’t be able to lend, and new money won’t be created. Lowering interest rates further makes little difference, and in theory, if interest rates went negative, then people would have an incentive to withdraw cash from the bank and hold it in vaults (with 0% interest) rather than hold it in a bank with negative interest.

This problem is known as the ‘Zero Lower Bound’, i.e. you can’t lower rates (much) below zero. To get around this problem, central banks around the world have used a range of ‘unconventional monetary policy’ tools, such as Quantitative Easing, in an attempt to boost spending.

Economists have assumed that the current low interest rates are a temporary response to a global financial crisis, and that once spending and the economic recovery resumes, central banks will move the rates back to where they were before the crisis. In other words, once everything returns to normal, the Zero Lower Bound will cease to be a problem.

But Haldane warned that low interest rates may actually be a permanent feature of the monetary system. For the last few decades, interest rates have gradually fallen:

“Over the past 30 years, however, world real [i.e. adjusted for inflation] interest rates have been in secular decline (Broadbent (2014)). At the dawn of the crisis, they had halved to around 2%. Since then they have fallen further to around zero, perhaps even into negative territory. With a 2% inflation target, that would now put nominal interest rates, on average over the cycle, at 2%.”

The problem is that if the normal interest rate will be 2%, and the Zero Lower Bound is, as the name suggests, at 0%, then the central bank doesn’t have a lot of scope to lower interest rates when it needs to boost the economy.

Common sense would say that this shows that interest rates have become ineffective as a monetary policy tool. Raising and lowering interest rates to encourage people to borrow more or less, and banks to create more or less money, is no longer effective. But Haldane suggests that if the policy hasn’t worked so far, we should try using more of it. If interest rates of 0.5% aren’t low enough, then maybe we should go to negative rates.

But again, this would give people an incentive to withdraw physical money from banks and hold that cash at home (since earning 0% on cash under the mattress is preferable to having say, -1% deducted from your account every year).

Haldane suggests that this could be prevented by abolishing physical cash. However, this would leave privately-issued bank deposits as the only form of money. People would likely object to the disappearance of any form of state-issued money. As Haldane says:

“Government-backed currency is a social convention, certainly as the unit of account and to lesser extent as a medium of exchange. These social conventions are not easily shifted, whether by taxing, switching or abolishing them.”

But what if paper currency was replaced by digital currency, issued by the central bank?

“One interesting solution, then, would be to maintain the principle of a government-backed currency, but have it issued in an electronic rather than paper form. This would preserve the social convention of a state-issued unit of account and medium of exchange, albeit with currency now held in digital rather than physical wallets. But it would allow negative interest rates to be levied on currency easily and speedily, so relaxing the ZLB constraint.”

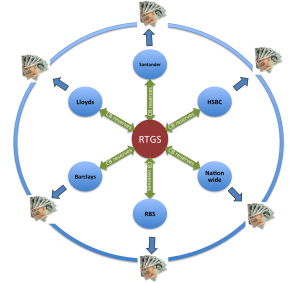

There are certainly strong arguments for allowing people to hold a digital version of central bank money. Currently members of the public have a choice of holding central bank money in physical form (coins and notes) or of holding electronic bank deposits, which are issued by commercial banks. But the public has no way of holding electronic central bank money, because the central bank only provides electronic accounts to other banks (and some financial sector companies). It’s close to impossible to function in society today without the use of electronic means of payment, but in order to hold money in electronic form, we are forced to hold that money at a bank.

If the central bank were to issue an electronic form of money, this would give people a choice of whether they wanted to entrust that money to a bank, or to hold it safe at the central bank.

But the weakest reason for a central bank to issue digital money is in order to abolish cash and levy negative rates. Central bankers need to wake up to the fact that interest rates – the tool they’ve used for the last few decades – is no longer the tool they should be using going forward. If the medicine doesn’t work, the correct approach is not to simply keep increasing the dosage, but to look at other medicines.

Haldane highlights the fact that state-issued digital currency is not technologically challenging:

“In one sense, there is nothing new about digital, state-issued money. Bank deposits at the central bank are precisely that.”

(These bank deposits at the central bank can only be held by other banks, so they are not available to the general public.)

However, Bitcoin is largely to thank for the fact that central banks have finally started thinking about issuing digital money:

“The technology underpinning digital or crypto-currencies has, however, changed rapidly over the past few years. And it has done so for one very simple reason: Bitcoin.”

However, I would argue that in this context Bitcoin is a distraction. The underlying technology that powers Bitcoin could be useful in payment systems and in a wide range of other uses. But central banks have been able to issue digital central bank money for as long as they’ve had networked computers; Bitcoin doesn’t change anything here, although it does provoke the debate.

Haldane moves on to more interesting questions:

“Whether a variant of this technology could support central bank-issued digital currency is very much an open question. So too is whether the public would accept it as a substitute for paper currency. Central bank-issued digital currency raises big logistical and behavioural questions too. How practically would it work? What security and privacy risks would it raise? And how would public and privately-issued monies interact?”

“These questions do not have easy answers. That is why work on central bank–issued digital currencies forms a core part of the Bank’s current research agenda (Bank of England (2015)). Although the hurdles to implementation are high, so too is the potential prize if the ZLB constraint could be slackened. Perhaps central bank money is ripe for its own great technological leap forward, prompted by the pressing demands of the ZLB.”

What is exciting about this is that the Bank of England now appears to be waking up (slowly) to the potential for issuing a digital form of cash. But Haldane’s fixation on the use of interest rates is short-sighted. There are far more interesting uses for digital central bank money.