A Response to Paul Krugman on “Is Banning Banking the Answer?”

Paul Krugman, the Nobel-prize* winning economist has written a commentary on Martin Wolf’s article “Strip banks of their power to create money”, in which Wolf advocates the policies that I and my co-author Andrew Jackson proposed in Modernising Money.

Krugman writes:

“The basic idea both writers share is that banks as we know them — institutions that issue promises to pay money on, or almost on, demand, while holding liquid assets that cover only a fraction of that potential demand — are inherently subject to runs, self-fulfilling losses of confidence. So they propose that we aim to eliminate such institutions; there would still be things we call banks, but they would simply be custodians of government-issued liquid assets.”

His criticism is that this argument ignores much of what went on during the 2007-2009 financial crisis:

“Wolf, unless I’m reading him wrong, seems to identify the whole issue with one particular form of short-term debt — bank deposits. This seems an oddly narrow view given the nature of the 2008 crisis, which involved very few runs on deposits but a massive run on shadow banking, especially repo — overnight lending that in a fundamental sense fulfilled the functions of deposit banking but also created the same kind of risks. Cochrane gets this, and calls for a “Pigouvian tax” — i.e., the kind of tax economics textbooks tell us we should have on pollution — imposed on any form of ‘run-prone short-term debt’.”

He has three suggestions:

“First, Wolf’s omission is a big one. If we impose 100% reserve requirements on depository institutions, but stop there, we’ll just drive even more finance into shadow banking, and make the system even riskier.”

This is a very valid warning. Banks can create money because the liabilities that they issue (i.e. the numbers that appear in the bank account of a borrower before he spend the loan) can be used to make payments to third parties. A sovereign money / full-reserve / 100% reserve style banking system prevents banks from issuing these liabilities; all money that is used to make payments will be in the form of electronic money or cash both issued by the Bank of England.

It is then hugely important to watch out for non-banks that start to create liabilities that look like and function as money. One example of this might be a mutual fund that allows customers to transfer their fund balances to other customers – in effective providing a means of payment. Or firms that promise customers instant withdrawals of their funds whilst being unable to make those payments in full. This is a job for the regulator. (The regulator would not need to spend so much time regulating banks in a reformed system, as the failure of those banks would not threaten the payments system, and the taxpayer would not be on the hook for bank failures.)

The other key point Krugman brings up is that the 2008 crisis was not in the main a banking crisis:

“This seems an oddly narrow view given the nature of the 2008 crisis, which involved very few runs on deposits but a massive run on shadow banking, especially repo — overnight lending that in a fundamental sense fulfilled the functions of deposit banking but also created the same kind of risks.”

Krugman rightly identifies that there weren’t many runs on traditional banks. This is true, for the simple reason that traditional bank deposits are insured (i.e. guaranteed) by government, whereas funds with other types of financial company are not. The appearance of finance ministers on television promising to use taxpayers’ money to guarantee all bank deposits can work wonders to stop a run on the banking system. There’s no equivalent guarantee for the non-banking system. Consequently, most individuals do not feel the need to withdraw their deposits when their bank looks like it might be in trouble.

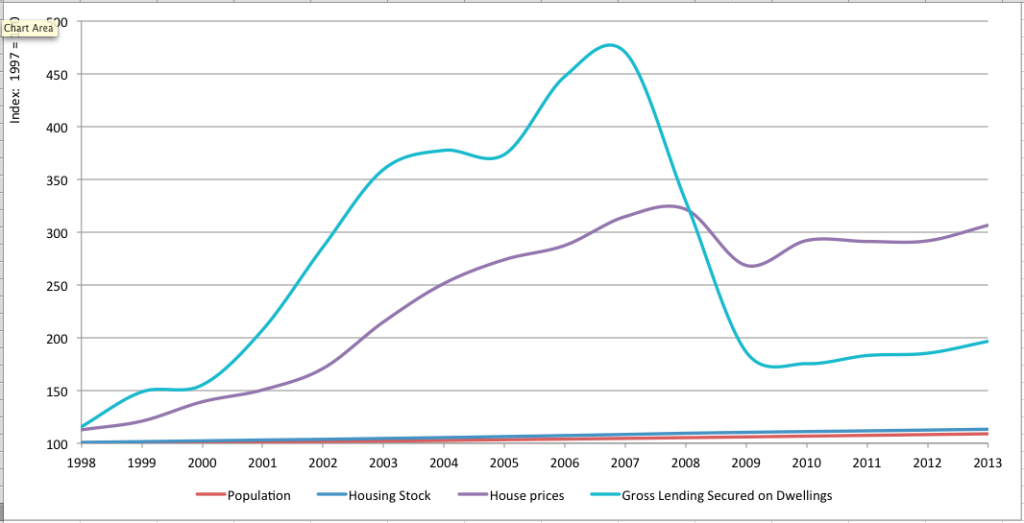

Perhaps more importantly, however, Krugman misses the way in which the actions of the traditional banking sector led to the run on shadow banking assets. The increase in house prices from the late 90s to 2007 were in large part the result of traditional banks lending huge amounts of money into the housing market. This lending increased both house prices and the amount of private debt in the economy, without increasing incomes. As private debt can’t continue to increase in excess of income forever, eventually things came to a head. In 2007-08 individuals started to default on their loans, resulting in the financial crisis. However, by this time the traditional banks had sold many of their mortgage assets to the shadow banks. Hence many of the problems of the 2007-08 crisis manifested themselves in the shadow banking sector. Yet it is important to remember that the housing bubble could never have happened without the private banks lending in the first place.

Krugman’s second comment is on John Cochrane’s proposal, which I’ll deal with in a separate article.

His third comment asks a question. I’ve bolded the key sentence:

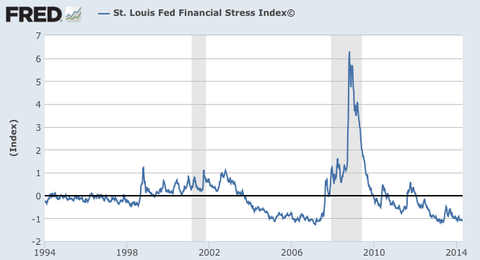

“Are we really sure that banking problems are the whole story about what went wrong? I’ve made this point before, but look at any measure of financial stress: what you see is a huge peak in 2008 that quickly went down:”

“Yet the quick return to normality in financial markets (achieved, to be sure, through bailouts and guarantees) did not produce a quick recovery in the real economy; on the contrary, we’re still depressed and many advanced countries are now on the edge of deflation, more than five years later. This strongly suggests that while bank runs may have brought things to a head, the problems ran deeper; in particular, I’m strongly of the view (based in part on Mian and Sufi’s work) that broader issues of excess leverage, and the resulting balance-sheet problems of many households, are key. And neither 100% reserves nor a repo tax would have addressed that kind of leverage.”

This is where (in our view) Krugman misses the point. The leverage (i.e. the huge build-up in the levels of household debt) is very much due to the design of the current banking system, which allows banks to create money as they make loans. In particular, the huge sums of money that banks create through mortgage lending has pushed up house prices to the point where we have historically high levels of unaffordability (and note that this is with the lowest levels of interest in centuries; it’s scary to imagine the situation with higher rates).

This chart below gives some indication of how mortgage lending can explode and push up house prices:

INDEXED RISE IN MORTGAGE LENDING:

I often hear the argument that people voluntarily took on huge mortgages to buy property. More likely most first time buyers were in the position of seeing house prices rise further and further out of reach. The fear of being permanently priced out and spending a life-time renting (which would leave you hundreds of thousands of pounds worse off by retirement age) drove people to buy. This is happening in London again today, and will soon be happening across the country. (In addition, much of the additional demand for mortgage lending came about due to many people seeing rising house prices as a way to make money through buy-to-let.)

Removing the ability of banks to create money will restrict mortgage lending and dampen bubbles. It could allow property prices to remain flat for a while whilst salaries catch up. There will still be systemic biases towards investing in property over say, real productive businesses, but these would need to be addressed by a) reforms to the Basel accords (which make it so that it costs around twice as much for a bank to make a business loan than a property loan) and b) some form of property or land-value taxation to dampen speculative bubbles.

Keeping property prices flat (or at least, stopping them from rising at 10%+ a year) would have limited the huge rise in household debt. So Krugman is wrong that “100% reserve”-style reforms would not have avoided the current level of household debt and leverage. Of course, safeguards would need to be in place to ensure that businesses still have access to the money they need to grow and invest. I will outline these in a subsequent blog post.

Even more importantly, the switch to the system proposed in Modernising Money would allow household debt to be reduced significantly, as new money is injected into the real economy and can be used to pay off some of the existing debts. (In contrast, in the current system, any repayment of debt to banks also reduces the amount of money in the economy. If people en masse repay their debts faster than new loans are made, the amount of new money creation slows, likely leading to a fall in spending, and potentially a recession.)

* The Nobel prize for economics is actually a prize awarded by the Swedish central bank which piggy backs on the credibility of the original Nobel prizes. More about that controversy here