UK banks benefited from £38bn ‘too big to fail’ state subsidy

Britain’s biggest banks benefited from a “too big to fail” subsidy from the taxpayer of £38bn last year, according to a leading economic thinktank, reads the Guardian on 17th December 2013.

The New Economics Foundation (Nef) said the big four – Barclays, HSBC and the bailed-out Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds Banking Group – were “failing to make themselves useful in the economy” despite the 10% rise in the value of the taxpayer’s implicit support.

Tony Greenham, head of finance and business at Nef, said the size of the implicit subsidy being provided to banks was staggering.

Greenham said: “UK taxpayers are still on the hook for the big banks.

“UK retail banking remains a curious kind of public-private partnership, but a highly unequal one – the public take the losses while private interests take the profits.

“Despite huge government subsidies, big banks still aren’t supporting the interests of the real economy.

“Even government attempts to bribe the banks into lending seem to have had little effect.”

You can read the whole article here.

The idea of something being too big to fail runs contrary to the very principle of capitalism – under a capitalist system a business that does badly is meant to fail!

The ‘too big to fail’ subsidy arose as a direct result of deposit insurance

When a company becomes insolvent, creditors to that company will usually lose a proportion of their money. But in the case of a bank, this would involve depositors only receiving a percentage of the full value of their account. However, in the UK (and in most other countries) the government guarantees that if a bank fails, the customers of that bank will be able to claim a certain percentage or a capped amount of their deposit back from the government.

The economic rationale for providing the government guarantee is simple: it’s many times cheaper and safer to rescue a bank than to let it fail. Because the central bank and government have franchised out the creation of money to the private banking sector. In the words of Martin Wolf, Chief Economics commentator of Financial Times:

“We have entrusted the private industry with the provision of the money supply and the payment system”

One problem with allowing a large bank to fail is that it could lead to problems at other banks. First, because banks owe each other large amounts of money a failure could lead to insolvencies at other banks due to the non-repayment of loans. This can lead to a cascade of bankruptcies throughout the entire system. Second, insolvency at one bank can lead to runs on solvent banks as depositors panic about their own bank’s position. The belief a bank is insolvent can become a self fulfilling prophecy, as a fire sale of assets reduces their value.

Another problem is that the payment system itself may be affected by bank insolvency: many banks do not have direct access to the high value payment systems, instead accessing them indirectly through a correspondent bank (known as a settlement bank). If the settlement bank became insolvent this could create problems in the payment system, as the ‘customer bank’ would not be able to make or receive payments.

As a result the government has to provide insurance and subsidies to both the banking sector and bank customers (e.g. lender of last resort, deposit insurance, too big to fail, etc). Consequently, the private sector is insulated from the costs of some of its actions, which instead fall on the government and society.

Deposit insurance has unintended consequences, chiefly by creating ‘moral hazard’ – those that lend to the bank pay less attention to how their money is used because they know that the bank won’t be allowed to go bust. This leads to the bank engaging in riskier behaviour than it otherwise would do – both in terms of the quantity of its lending (i.e. its leverage) and who it lends to. This makes banks more likely to need the insurance in the first place.

However, insurance also results in the banks receiving a subsidy – those that lend to the bank (including depositors) are willing to accept lower interest rates on their loans than they otherwise might, because the loan is less risky to them. Instead, it is the government, and by implication the taxpayer, that underwrites the risk of the loan going bad.

Large banks fully understand that deposit insurance means that if they become insolvent, the choice facing government is between repaying all their customers due to deposit insurance, or rescuing the bank through an ‘injection of capital’ (a bailout). In practice, it will always be many times cheaper and safer to rescue a bank that to let it fail. This knowledge will lead the bank to take higher risks, knowing full well that the government will be unable to afford not to rescue it if it should fail. The larger the bank, the greater the cost to government of allowing it to fail, and the more confident the bank will be that it has a guaranteed safety net even if the risks it takes backfire and it becomes insolvent. Banks will therefore lend greater amounts and lend to riskier borrowers than they otherwise would do, which will in turn lead to a larger money supply.

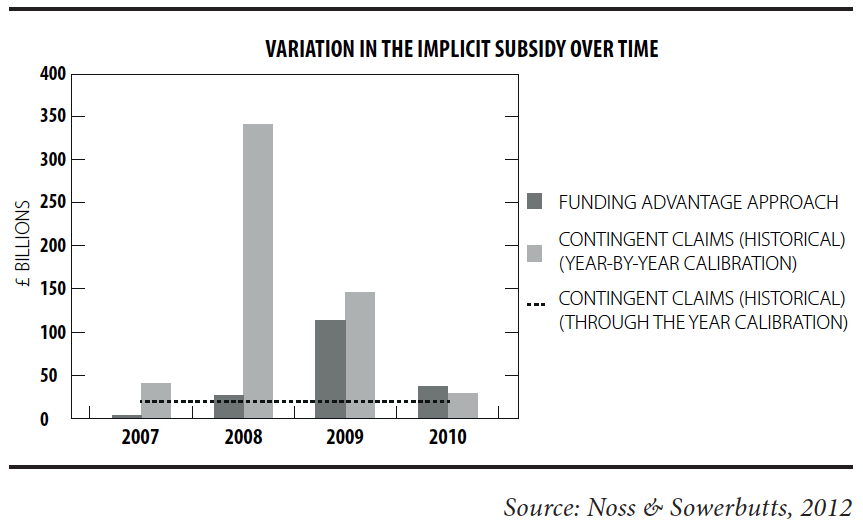

The Bank of England has calculated that some years this subsidy is worth in excess of £300bn (Noss & Sowerbutts, 2012) (although this figure depends on the method used to calculate the subsidy).

The subsidy tends to be higher in years where the banks are seen as more likely to need government support. Noss and Sowerbutts conclude that, “despite their differences, all measures point to significant transfers of resources from the government to the banking system.”

In some years the value of the subsidy has been high enough that it is difficult to see how the banks would have been profitable without it. As well as transferring resource from the public to the banking sector, the subsidy also distorts competition between banks – the larger/more systemically important a bank is, the more likely it is to be rescued if it finds itself in distress. As a result large banks receive a bigger implicit subsidy, lowering the rate of interest they have to pay to borrow. This places large banks at a competitive advantage to smaller banks, stifling new entrants and competition. Furthermore larger banks that offer substandard products are less likely to be forced out of the market, (as they would be in other industries), reducing social welfare.

In conclusion, the inherent instability of the banking sector and the negative impacts of this instability compels the government to provide insurance, which, due to moral hazard, actually increases the risks that banks take – so increasing financial instability.

In a reformed banking system taxpayers would never again have to bail out a bank

Under a banking system reformed according to the Positive Money proposals, as described in the book Modernising Money, banks will be allowed to fail, rather than being rescued by the taxpayer. They could no longer rely on government bailouts if they become insolvent.

This would have the effect of removing a subsidy to the banking sector, as well as the added benefit that banks will be far more concerned with the types of loans they are making.

With money no longer issued when banks make loans, banks will be allowed to fail and the ‘too big to fail’ subsidies for large banks will disappear.

Read more: Ending Too Big To Fail