Quantitative Easing: What happened to the money?

Quantitative Easing (QE) created reserves to pay for bonds (eventually entirely government bonds) bought by the Bank of England from the private sector. The expectation was that those who sold the bonds would use the money to buy new bonds issued by private corporations to replace bank lending which had dried up.

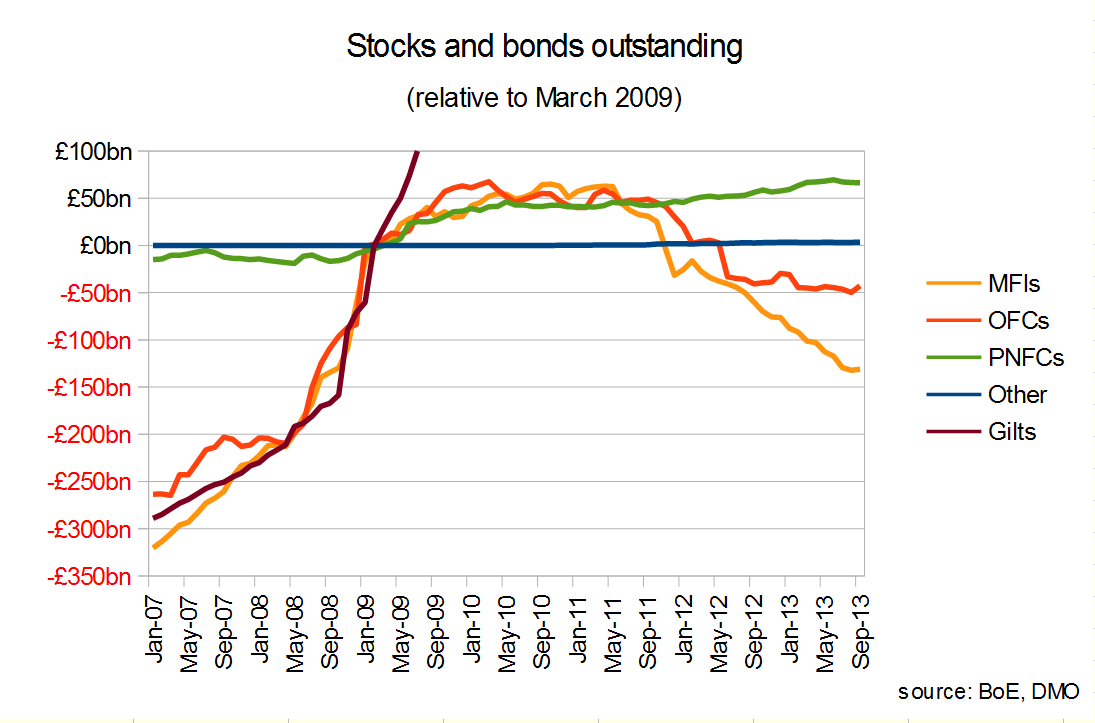

The first chart shows how the levels of securities outstanding have changed relative to their levels in March 2009, the start of QE.

In the run-up to the crisis, private non-financial corporations (PNFCs) were not raising any new money by issuing bonds or shares, whilst banks and other financial corporations (OFCs) were each issuing new securities at a similar rate to the government. These rates accelerated sharply after Lehmans’ collapse in September 2008, but slowed markedly at the onset of QE (although the gilt issue settled at around £15bn a month – by September 2013, the par value of gilts in issue had increased by £825bn since the onset of QE). PNFCs however, did start to issue bonds to take advantage of the QE money.

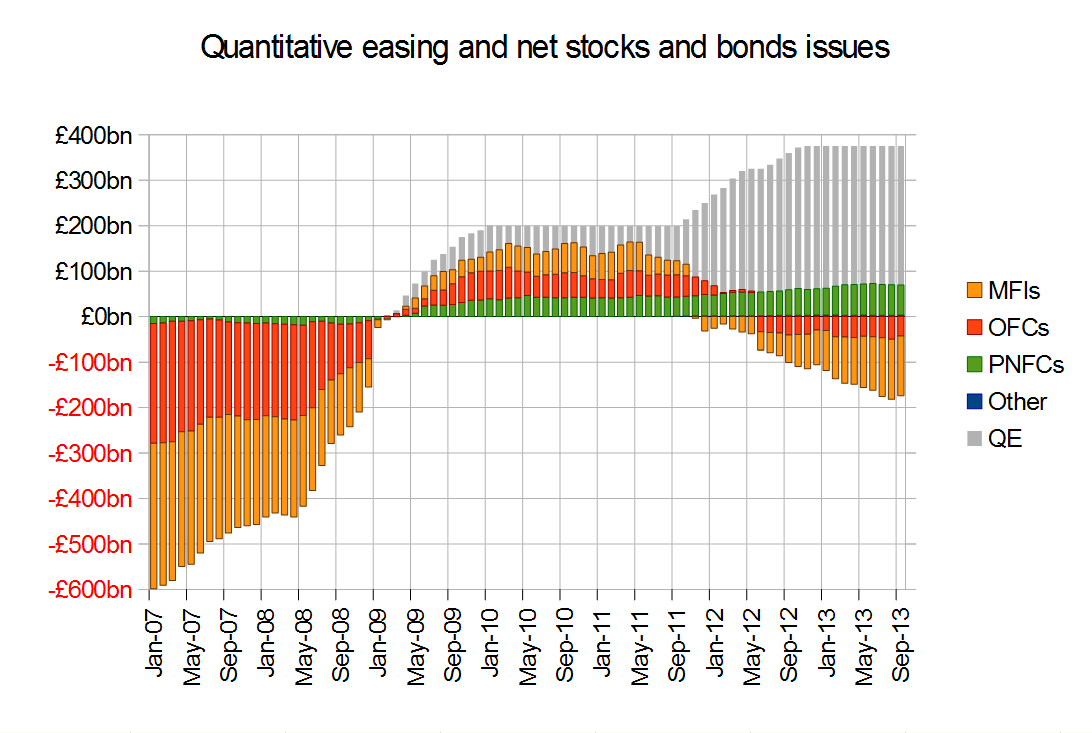

The second chart stacks the bond issues together to compare the amounts raised with the money made available by QE.

This shows that for the first round of QE, around 75% of the money was taken up through bond issues by the private sector, although the finance sector took the lions’ share. With the onset of the second round, however, the banks began to pay off their bonds, and with the third round, so did the other financial corporations. The PNFCs, however, continue to raise money through this route.

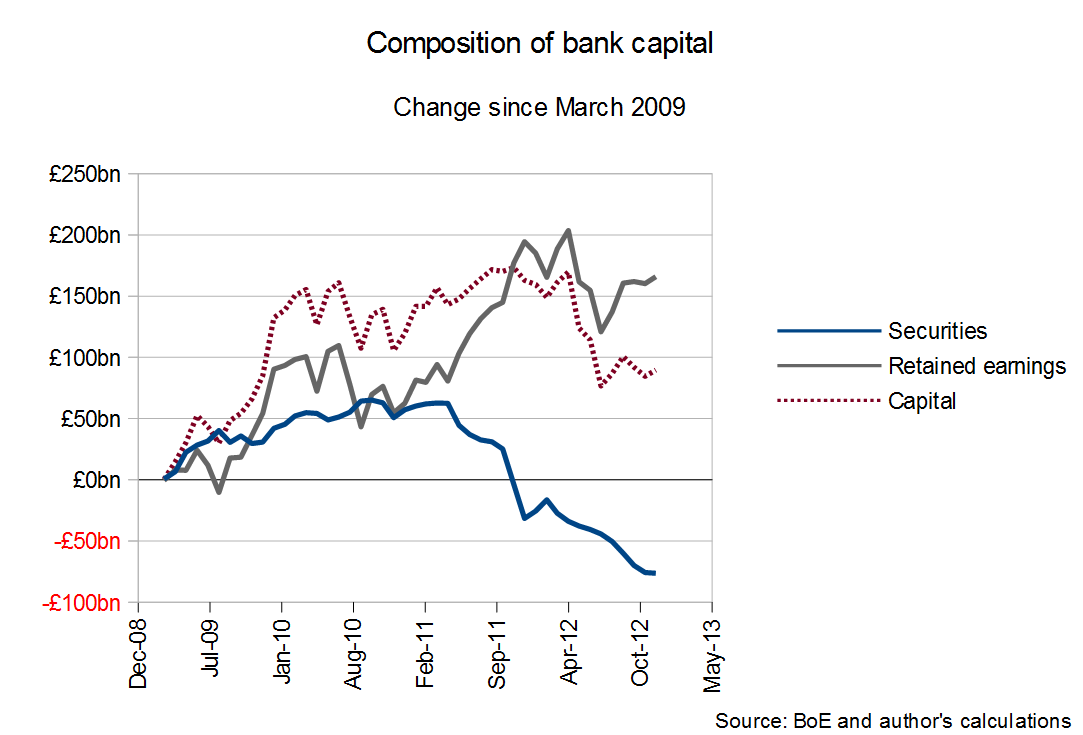

The third chart shows that the banks were able to retire their debt funding because of the accumulation of retained earnings, which stabilised their levels of capital, although these slipped back during the second half of last year.

The other financial corporations were presumably also able to redeem their bonds by accumulating retained earnings.

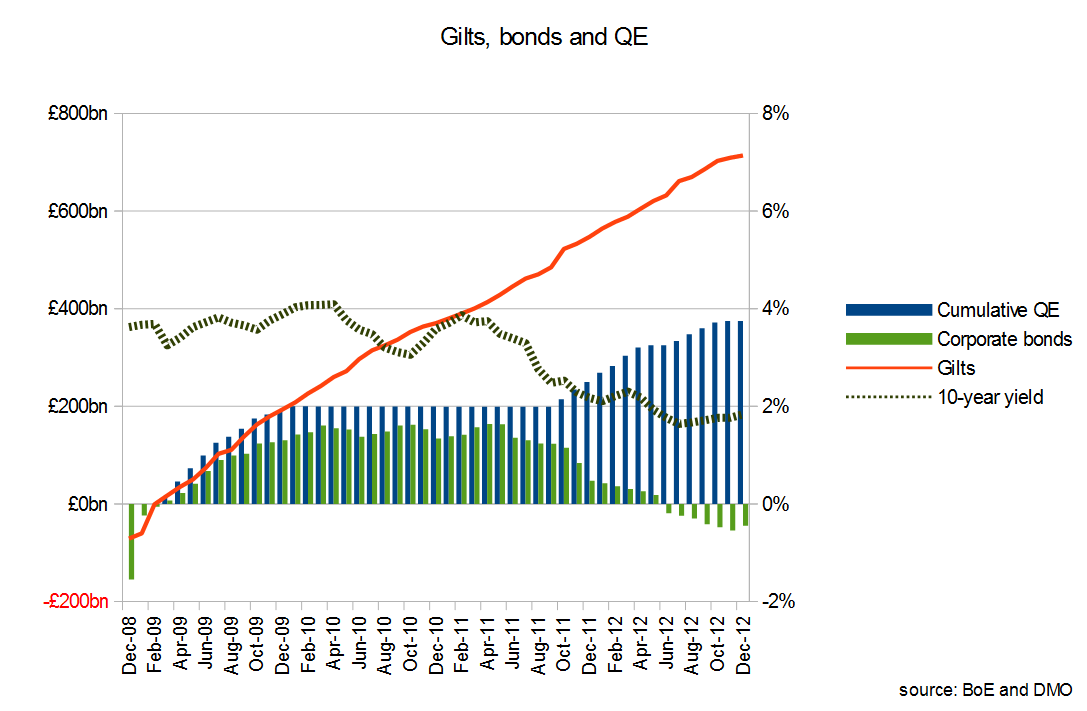

It can be surmised from this, that the balance of the money from the first round of QE, and substantially all of that from subsequent rounds was used to purchase gilts, and the fourth chart shows that there were plenty to choose from, with falling yields providing attractive opportunities for capital gains.

In conclusion, quantitative easing has had three effects:

by creating an artificial demand for gilts it increased their market price, thereby reducing yields and increasing the attractiveness of higher-yielding corporate bonds;

in a time of uncertain asset valuations it enabled the financial sector to raise temporary loss-absorbing loan capital by issuing bonds, which gave them the breathing space to build up their equity; and

it provided for those corporations who were able to manage the issue of bonds a source of debt funding to replace the bank lending which had dried up due to that uncertainty.